Balineesch dansmeisje in rust (A dancing-girl of Bali, resting) c 1925

Dutch East Indies and Indonesian photography, and more broadly Asia-Pacific photography, has been a burgeoning area of interest, research and collecting for some time now. Although this is far from my area of expertise, with the quality of the work shown in this posting, you can understand why. Since 2005, “the National Gallery of Australia’s Asian photographs collection has grown to nearly 8000 and in excess of 6500 prints are from Indonesia.”

Thilly Weissenborn

NOTES

Dutch East Indies and Indonesian photography, and more broadly Asia-Pacific photography, has been a burgeoning area of interest, research and collecting for some time now. Although this is far from my area of expertise, with the quality of the work shown in this posting, you can understand why. Since 2005, “the National Gallery of Australia’s Asian photographs collection has grown to nearly 8000 and in excess of 6500 prints are from Indonesia.”

Absolutely beautiful tonality to the prints. They seem to have a wonderful stillness to them as well.

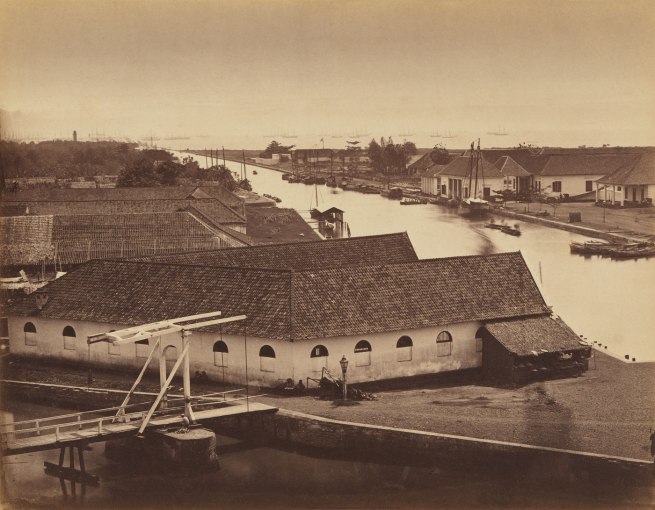

Woodbury & Page

established Jakarta 1857-1900

Batavia roadsteadc. 1865

Albumen silver photograph

19.4 x 24.5 cm

Collection National Gallery of Australia

Batavia roadsteadc. 1865

Albumen silver photograph

19.4 x 24.5 cm

Collection National Gallery of Australia

Dirk Huppe

Indonesia 1867-1931

O Kurkdjian & Co

Established Surabaya, Java 1903-1935

Mature canes, fertilized with artificial guano, Java Fertilizer Co.,

Semarang 1914

Carbon print photograph

74.6 x 99.6 cm

Collection National Gallery of Australia

O Kurkdjian & Co

Established Surabaya, Java 1903-1935

Mature canes, fertilized with artificial guano, Java Fertilizer Co.,

Semarang 1914

Carbon print photograph

74.6 x 99.6 cm

Collection National Gallery of Australia

S. Satake

Japanese, working Indonesia 1902 – c. 1937

Eruption

Java c. 1930

Gelatin silver photograph

16.2 x 21.8 cm

Collection National Gallery of Australia

Eruption

Java c. 1930

Gelatin silver photograph

16.2 x 21.8 cm

Collection National Gallery of Australia

“While Indonesia might be the second most popular destination for outbound Aussies, the history of the Indonesian archipelago’s diverse peoples and the colonial era Dutch East Indies, remains unfamiliar. In particular the rich heritage of photographic images made by the nearly 500 listed photographers at work across the archipelago in the mid 19th – mid 20th century, is poorly known, both in the region and internationally.

The Gallery began building its Indonesian photographic collection in 2006. It is unique in the region: the largest and most comprehensive collection excluding the archives of the Dutch East Indies in the Netherlands. It was not until the late 1850s with the arrival of photographs printed on paper from a master glass negative, that images of Indonesia – the origin of nutmeg, pepper and cloves, much desired in the West – began circulating worldwide.

Australia had a minor role in the history of photography in Indonesia. A pair of young British photographers, Walter Woodbury and James Page (operators of the Woodbury & Page studios located in the Victorian goldfields and Melbourne) arrived in Jakarta in 1857. From around 1900 a trend toward more picturesque views and sympathetic portrayals of indigenous people appeared. Old images were given new life as souvenir prints and sold through hotels and resorts or used for cruise ship brochures.

A particular feature of Garden of the East is the display of family albums. Both amateur and professional images in the Indies were bound in distinctive Japanese or Batik-patterned cloth boards as records of a colonial lifestyle. Hundreds of these once-treasured narratives of now lost people ended up in the Netherlands in the 1970s and 80s in estate sales of former Dutch colonial and Indo (mixed race) family members who had returned or immigrated after the establishment of the Republic of Indonesia in 1945.”

Text from the National Gallery of Australia website

S. Satake

Japanese, working Indonesia 1902 – c. 1937

Women on road to Buleleng

Bali c. 1928

Gelatin silver photograph

16.2 x 22.0 cm

Collection National Gallery of Australia

Women on road to Buleleng

Bali c. 1928

Gelatin silver photograph

16.2 x 22.0 cm

Collection National Gallery of Australia

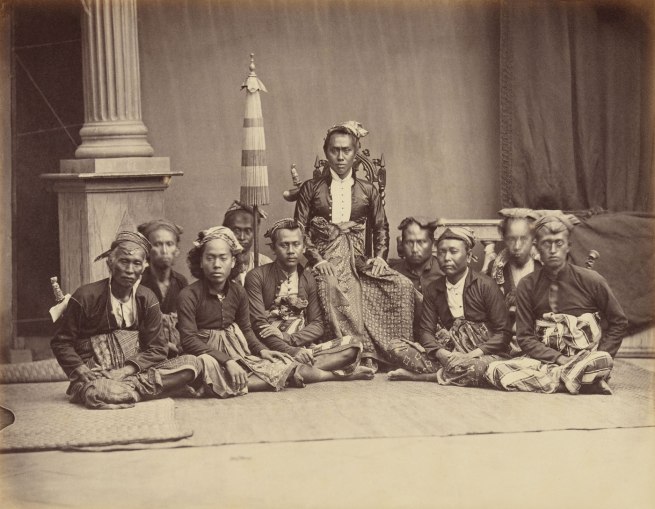

Woodbury & Page

established Jakarta 1857-1900

Gusti Ngurah Ketut Jelantik, Prince of Buleleng with his entourage in Jakarta in 1864 on the visit of Governor-General LAJW Sloet van de Beele

1864

Albumen silver photograph

Collection National Gallery of Australia

Gusti Ngurah Ketut Jelantik, Prince of Buleleng with his entourage in Jakarta in 1864 on the visit of Governor-General LAJW Sloet van de Beele

1864

Albumen silver photograph

Collection National Gallery of Australia

“Garden of the East: Photography in Indonesia 1850s-1940s is the first major survey in the southern hemisphere of the photographic art from the period spanning the last century of colonial rule until just prior to the establishment of the Republic of Indonesia in 1945. The exhibition provides the opportunity to view over two hundred and fifty photographs, albums and illustrated books of the photography of this era and provides a unique insight into the people, life and culture of Indonesia. The exhibition and accompanying catalogue reveals much new research and information regarding the rich photographic history of Indonesia. Garden of the East is on display in Canberra only.

The exhibition is comprised of images created by more than one hundred photographers and the majority have never been exhibited publicly before. The works were captured by photographers of all races, making images of the beauty, bounty, antiquities and elaborate cultures of the diverse lands and peoples of the former Dutch East Indies. Among these photographers is the Javanese artist Kassian Céphas, whose genius as a photographer is not widely known at this time, a situation which the National Gallery of Australia hopes to address by growing the collection of holdings from this period and by continuing to stage focused exhibitions such as Garden of the East.

As was the case in other Southeast Asian ports, the most prominent professional photographers at work in colonial Indonesia came from a wide range of European backgrounds until the 1890s, when Chinese photography studios began to dominate. The exhibition focuses on the leading foreign studios of the time, in particular Walter B Woodbury, one of the earliest photographers at work in Australia in the 1850s as well as the Dutch East Indies. However Garden of the East also includes images created by lesser known figures whose work embraced the new art photography styles of the early twentieth century including: George Lewis, the British chief photographer at the Surabaya studio founded by Armenian Ohannes Kurkdjian, the remarkable German amateur photographer Dr Gregor Krause; American adventurer and filmmaker André Roosevelt; and the only woman professional known to have worked in the period, Thilly Weissenborn, whose works were intertwined with the tourist promotion of Java and Bali in the 1930s. Chinese studios are well-represented, although little is known of their founders and many employed foreign photographers.

Frank Hurley is the sole Australian photographer represented in the exhibition. Hurley is noted as the only Australian known to have worked in Indonesia before the Second World War and toured Java in mid-1913, on commission to promote tourist cruises from Australia to the Indies for the Royal Packet Navigation Company.

“We are delighted to host this exhibition and believe that Australia’s geographic, political and cultural position in the Asia-Pacific region makes it very appropriate that the National Gallery of Australia should celebrate the rich and diverse arts of our region,” said Ron Radford AM, Director, National Gallery of Australia. “A dedicated Asia-Pacific focused policy has been long-held by the Gallery, but it was not until 2005 that we focused on early photographic art of the region. Progress, however, has been rapid and all the photographs in Garden of the East have been recently acquired for the National Gallery’s permanent collection,” he said.

“From a small holding in 2005 of less than two hundred photographs from anywhere in Asia, of which only half a dozen were by any Asian-born photographers, the National Gallery of Australia’s Asian photographs collection has grown to nearly 8000 and in excess of 6500 prints are from Indonesia,” Ron Radford said.

“Garden of the East presents images, both historic and homely and is a ‘time travel’ opportunity to visit the Indies through more than two hundred and fifty works on show, made by both professional and amateur family photographers. Images as diverse as the Indonesian archipelago itself, which was once described by nineteenth century travel writers as the Garden of the East,” said Gael Newton, Senior Curator of Photography, National Gallery of Australia and exhibition Curator.

Garden of the East: Photography in Indonesia 1850s-1940s follows the large 2008 survey exhibition Picture Paradise: Asia-Pacific photography 1840s-1940s [the website includes an excellent essay - Marcus]. This was the first of the new Asia-Pacific collection focus exhibitions. In 2010, the Gallery staged an early photographic portrait exhibition to coincide with a conference hosted in partnership with the Australian National University entitled Facing Asia. A number of other small Asian collection shows have also been held since 2011.

The National Gallery of Australia is delighted to stage this exhibition to coincide with the Focus Country Program, an initiative organised by the Australian Government’s key cultural diplomacy body, the Australia International Cultural Council. The AICC has chosen Indonesia as its Focus Country for 2014 and will organise a series of events across the Indonesian archipelago to promote Australian arts and culture, as well as our credentials in sport, science, education and industry. This exhibition will also mark the 40th anniversary of dialogue relations between Australia and the Association of South East Asian Nations. The National Gallery of Australia is proud to be presenting an exhibition of Indonesian photography in celebration of Australia’s close cultural relations with Indonesia and the Asia-Pacific region.”

Press release from the National Gallery of Australia website

Kassian Céphas

Indonesia 1845-1912

Man climbing the front entrance to Borobudur

Central Java 1872

Albumen silver photograph

22.2 x 16.1 cm

Collection National Gallery of Australia

Man climbing the front entrance to Borobudur

Central Java 1872

Albumen silver photograph

22.2 x 16.1 cm

Collection National Gallery of Australia

Kassian Céphas

Indonesia 1845-1912

Young Javanese woman

c. 1885

Albumen silver photograph

13.7 x 9.8 cm

Collection National Gallery of Australia

Young Javanese woman

c. 1885

Albumen silver photograph

13.7 x 9.8 cm

Collection National Gallery of Australia

“Garden of the East: photography in Indonesia 1850s-1940s offers the chance to see images from the last century of colonial rule in the former Dutch East Indies. It includes over two hundred photographs, albums and illustrated books from the Gallery’s extensive collection of photographic art from our nearest Asian neighbour.

Most of the daguerreotype images from the 1840s, the first decade of photography in Indonesia, are lost and can only be glimpsed in reproductions in books and magazines of the mid nineteenth century. It was not until the late 1850s that photographic images of Indonesia – famed origin of exotic spices much desired in the West – began circulating worldwide. British photographers Walter Woodbury and James Page, who arrived in Batavia (Jakarta) from Australia in 1857, established the first studio to disseminate large numbers of views of the country’s lush tropical landscapes and fruits, bustling port cities, indigenous people, exotic dancers, sultans and the then still poorly known Buddhist and Hindu Javanese antiquities of Central Java.

The studios established in the 1870s tended to offer a similar inventory of products, mostly for the resident Europeans, tourists and international markets. The only Javanese photographer of note was Kassian Céphas who began work for the Sultan in Yogyakarta in the early 1870s. In late life, Céphas was widely honoured for his record of Javanese antiquities and Kraton performances, and his full genius can be seen in Garden of the East.

Most of the best known studios at the turn of the century, including those of Armenian O Kurkdjian and German CJ Kleingrothe, were owned and run by Europeans. Chinese-run studios appeared in the 1890s but concentrated on portraiture. Curiously, relatively few photographers in Indonesia were Dutch. From the 1890s onward, the largest studios increasingly served corporate customers in documenting the massive scale of agribusiness, particularly in the golden economic years of the Indies in the early to mid twentieth century. From around 1900, a trend toward more picturesque views and sympathetic portrayals of indigenous people appeared. This was intimately linked to a government sponsored tourist bureau and to styles of pictorialist art photography that had just emerged as an international movement in Europe and America. As photographic studios passed from owner to owner, old images were given new life as souvenir prints sold at hotels and resorts and as reproductions in cruise-ship brochures.

Amateur camera clubs and pictorialist photography salons common in Western countries by the 1920s were slower to develop in Asia and largely date to the postwar era. Locals, however, took up elements of art photography. Professionals George Lewis and Thilly Weissenborn (the only woman known from the period) and amateurs Dr Gregor Krause and Arthur de Carvalho put their names on their prints and employed the moody effects and storytelling scenarios of pictorialist photography. Krause was one of the most influential photographers. He extensively published his 1912 Bali and Borneo images in magazines and in two books in the 1920s and 1930s, inspiring interest in the indigenous life and landscape as well as the sensuous physical beauty of the Balinese people.

Postwar artists and celebrities – including American André Roosevelt, who used smaller handheld cameras – flocked to the country to capture spontaneity and daily life around them, to affirm their view of Bali as a ‘last paradise’ , where art and life were one. In 1941, Gotthard Schuh published Inseln der Götter (Islands of the gods), the first modern large-format photo-essay on Indonesia. While romantic, the collage of images and text in Schuh’s book presented a vital image of the diverse islands, peoples and cultures that were to be united under the flag of the Republic of Indonesia in 1949.

A particular feature of Garden of the East is a selection of family albums bound in distinctive Japanese or Batik patterned cloth boards as records of a colonial lifestyle (for the affluent) in the Indies. Hundreds of these once treasured narratives of now lost people ended up in the Netherlands in the 1970s and 1980s in estate sales of former Dutch colonial and Indo (mixed race) family members who had returned or immigrated after the establishment of the Republic of Indonesia.”

Text from the National Gallery of Australia Artonview 76 Summer 2013

Sem Céphas (Indonesia 1870 – 1918)

Portrait of a Javanese woman

c.1900

Gelatin silver photograph, colour pigment hand painted photograph image

38.5 x 23.8 cm

Purchased 2007

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

c.1900

Gelatin silver photograph, colour pigment hand painted photograph image

38.5 x 23.8 cm

Purchased 2007

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Gotthard Schuh

Inseln der Götter (Islands of the gods) [book cover]

1941

Hardcover w/dust jacket

154pp, text in German

Plates in photogravure

28.5 x 22.5 cm

1941

Hardcover w/dust jacket

154pp, text in German

Plates in photogravure

28.5 x 22.5 cm

Thilly Weissenborn

Indonesia 1902 – Netherlands 1964

A dancing-girl of Bali, resting

c. 1925

Photogravure

21.1 x 15.9 cm

Collection National Gallery of Australia

A dancing-girl of Bali, resting

c. 1925

Photogravure

21.1 x 15.9 cm

Collection National Gallery of Australia

Unknown photographer

Working Bali 1930s

I Goesti Agoeng Bagoes Djelantik, Anakagoeng Agoeng Negara, Karang Asem

Bali 1931

Gelatin silver photograph

14.0 x 9.7 cm

Collection National Gallery of Australia

I Goesti Agoeng Bagoes Djelantik, Anakagoeng Agoeng Negara, Karang Asem

Bali 1931

Gelatin silver photograph

14.0 x 9.7 cm

Collection National Gallery of Australia

|

Thilly Weissenborn Balinese women carrying water, c 1922. Photogravue |

Thilly Weissenborn

The Romance of the Indies

Adrian Vickers

If nineteenth and early twentieth-century male photographers established a way of showing the Dutch East Indies in the light of a benevolent colonialism bent on preserving quaint cultures and establishing an imperial sense of space, Thilly Weissenborn, the first major female photographer of the Indies, introduced a fundamental transformation in European ways of seeing the region.

Through her photography, she infused the earlier vision with a sense of the romance of the islands—the Indies as wish fulfillment. This warm, extroverted woman of dry humor and ready ability to make friends was more of a child of the Indies than she was Dutch.1 She was born in 1889 in Kediri, East Java, of German-born, naturalized Dutch parents who owned a coffee plantation there, and later in Tanganyika. She spent less time in the early part of her life in the Netherlands than in Java.

The beginning of Weissenborn's photographic career is something of a mystery. One elder sister, Else, had studied photography in Paris and set up a studio in the Hague by the time Thilly was fourteen, and we know that the younger sister was working in the Kurkdjian studio in Surabaya in 1917. However, a number of Kurkdjian photographs later attributed to Weissenborn appear in H. H. Kol's momentous 1914 exposition of Bali, Sumatra and Java.2 Most of the photographs in this book lack the warmth and glowing light of Weissenborn's later work in Bali; the poses of the men and women are particularly lacking the grace she brought to such images.

For example, the image of two men beginning a cockfight is very stiff, the participants and surrounding gamblers are frozen, waiting for instrucrions from behind the camera lens. The man on the left, with a feather of a defeated cock under his hat for good luck, glances away from the supposed focus of masculine attention—the matching of cock against cock before one meets his death.

Weissenborn was trained by the Kurkdjian studio after the death of its Armenian founder. She worked under the supervision of the skilled English craftsman, G. P. Lewis,3 and her apprenticeship included touching up photographs and a fulll range of technical work. The studio had thirty employees, European and native, and she was one of only two women.4 In 1917, when she moved to Garut, in the nest of hill stations of West Java, she set up her own studio, "Lux." It was originally a part of a pharmacy owned by Denis G. Bulder, but she moved it to a separate location in 1920.

From that time onward, Weissenborn began to mark her work with a special lyrical quality. The views of her base at Garut all display the cool misty air of the quiet hills to which the overdressed and proper Dutch escaped from the sultry coast. The formality of the Governor-General's palace at nearby Bogor, the tenderness of European mothers with their children and the uncertain spontaneity of colonial tennis parties provided her bread and butter at the time. More heart went into her long vistas of the hills and the scenes of mountain village life as a rural idyll. In these, she portrayed single native figures in the fore or middle-ground of scenes that stretch out from comfortable Dutch gardens to distant volcanoes. In such views, she was seeking the magical qualities of the landscape, a special communion with nature that was different from what Europe had to offer.

From that time onward, Weissenborn began to mark her work with a special lyrical quality. The views of her base at Garut all display the cool misty air of the quiet hills to which the overdressed and proper Dutch escaped from the sultry coast. The formality of the Governor-General's palace at nearby Bogor, the tenderness of European mothers with their children and the uncertain spontaneity of colonial tennis parties provided her bread and butter at the time. More heart went into her long vistas of the hills and the scenes of mountain village life as a rural idyll. In these, she portrayed single native figures in the fore or middle-ground of scenes that stretch out from comfortable Dutch gardens to distant volcanoes. In such views, she was seeking the magical qualities of the landscape, a special communion with nature that was different from what Europe had to offer.

In the early 1920s, Weissenborn brought the romantic qualities she had developed in Garut to bear on the mountains, temples, women and princes of the island of Bali. She became most famous for this work, which was produced for a new tourist industry the Dutch wished to establish. From this time onward, a range of magazines, books and pamphlets were put out by tourist authorities and travel writers. These were designed to attract travelers to the East Indies by showing the exotic cultures of the islands tamed by colonialism, which in turn saw itself as preserving lavish indigenous cultures from the depredations of the modern world.

Although originally not considered important in the plans for tourism, Bali grew to be one of the keystones of that industry, and Weissenborn's photographs helped to give it that special aura by presenting its culture in the most exotic terms. In her Bali photographs, the tamed nature she captured in the hill stations of Java becomes one with the rich ornamentation of a temple gate, or blends into a sacred bathing place. A different kind of communion with nature, one centered around these lush temples and their art, made Balinese spirituality the epitome of the tropical East.

To combine nature and culture, Weissenborn frames her images of the baroque temple at Sangsit with frangipani branches, seeking similarities between the leaves of the ornamental silhouette and those of the tree. In a scene of an inner temple, she combines bright backlighting with the whiteness of ritual umbrellas and the holy gesture of prayer led by the Brahman high priest. The gestures of the assembled congregation move the observet's gaze upward to the sky as much as to the shrine, and they help to reinforce the clear break in the two halves of the composition.

The seated humans emerge out of the shadows of the platforms and coverings at the extreme left, while on the other side the whiteness is reinforced by the plates on the middle shrines, the cloth around the shrine to which worship is directed and the offerings set on a raised platform in the foreground. The shapes of the plaited leaves of the offerings are similar to those of the palm and pandus leaves in the background, giving a strong sense of the naturalness of Balinese religion, despite its strange and culturally rich qualities.

The ideal spirituality presented in this photograph is also present in Weissenborn's romantic images of Balinese men and women. Unlike many of the male photographers of Bali in the 1920s and 1930s, she avoided the prurience given to images of Bali's bare-breasted women and was concerned with showing the women's dignity and self-possession. In her image of two women along a roadside, this dignity comes through in the erectness of the woman carrying the pot on her head, a stance emphasized by her thin, straight sarong and sash, the downward, half-embarrassed movement of the second woman and the line of the tree to one side.

Ironically, these same images were easily appropriared into the general idea of Bali as the Island of Bare Breasts, the title of a French novel of the time. Given the abundance of images of semi-naked Balinese women produced from the 1920s on, it is not surprising that Weissenborn was unable to change substantially the masculine bias of this generalized image, but she had a far greater impact with her best-known photograph, that of a young dancing girl seated before a gong. This photograph was frequently reproduced in 1920s Dutch tourist literature and has subsequently been in the literature that continues to flood out about Bali.5 It captures that mysterious, ineffable quality of Bali—the inscrutable oriental culture of the island, rich but not threatening, that made it a place to which Europeans could escape from the drabness of their home.

Weissenborn's photograph of Gusti Bagus Jlantik, the intellectually able, short but handsome "self ruler" of the eastern Balinese state of Karangasem, captures her deep passion for understanding the inner spiritual qualities of the Indies through its exemplary characters. He was the Balinese ruler most favored by the Dutch, but also part of the new development of elite Indonesian self-assertion.

One of a series of portraits of Javanese and Balinese aristocrats done by Weissenborn during the 1920s, the photograph captures his fully confident gaze ditected back into her European camera, an assertion of a religiously and culturally confident leader of Indonesian society. His costume and setting display the nature of this indigenous leadership-traditionally Balinese in the widely-folded head-cloth set with a gold flower on one side and the flourish of brocaded breast-cloth at the front worn over a European-style jacket with Balinese ornamental gold edging. He is sitting on a gaudy European chair, a kind of extravagant statement in itself about the noble appropriation of European styles of display into an expression of local identity.

Extravagant princes, assertive and mysterious women and lavish temples combined with lush spreading landscape to make Weissenborn's Indies a place of dreaming romance. The romance was there to lure Europeans into a place so fantastic as to take them out of themselves. Bali served the narrow material interests of tourist development; but, for Weissenborn, her romantic photography was a way of telling others about the qualities of the Javanese and Balinese peoples and cultures that she had discovered for herself. She communicated the deeper spiritual values she read into the scenes and people she photographed.

NOTES

- For further information on her life and work, see Ernst Drissen, Vastgelegd voor later: Indische foto's (lQlj-1042) van ThiUy Weissenborn.Amsterdam: Sijthoff, 1983.

- H. H. Kol, Drei maal dwards door Sumatra en Java, met zwerftochten door Bali, Rotterdam: Brusse, 1914; cf, Drissen, Vastgelegd, 10. 13.

- Drissen, Vastgelegd, 12-13.

- Ibid., undated photo, 13.

- For images of Bali and tourism, see A. Vickers, Bali: A Paradise Created, Ringwood, Victoria: Penguin, 1989/Singapore: Periplus, 1990, see page 203 for an analysis of this photograph.

|

Thilly Weissenborn Balinese cockfight, c 1920. |

|

Thilly Weissenborn Balinese praying in a family courtyard, Bali, c. 1920. |

|

Thilly Weissenborn Gusti Bagus Jelantik, King of Karangasem, Bali, c 1923. |

|

Thilly Weissenborn Beiji temple with ornately carved gateway, Sangsit, Northern Bali, c. 1920. |

![Gotthard Schuh. 'Inseln der Götter' (Islands of the gods) [book cover] 1941](http://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/06/insel-de-gotter.jpg?w=655)