‘Miloň Novotný [A.G. Hughes (ed.), Libor Fára (graphic design)], Londýn, Prague, Mladá Fronta, 1968, 19.5 x 21 cm (7.75 x 8.5 ”), 136 pp.

With many thanks to Mr Alfonso Melendez

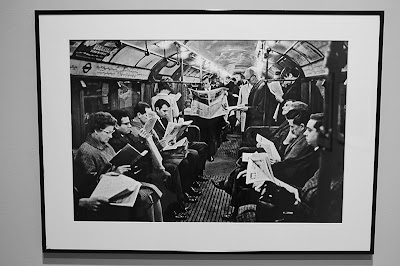

"Here our ‘dear, damned, deceptive city’ is portrayed uniquely and novelly,” wrote the British journalist A. G. Hughes for the album London / The Photography of Miloň Novotný. This book, first published in 1968, has retained a timeless quality. Yet we need not have been there ourselves to appreciate the pre-eminence with which the photographer reproduced the cosmopolitan port on the Thames estuary and, in doing so, uniquely captured the mood of a city blazing a trail through the 1960s. That is not to say that this extremely complex subject is limited to topography. A decay, of sorts, in the prominence of the British empire was reflected in the souls of its inhabitants. Miloň Novotný recognised this and conveyed it in his singular way. This book is revisited not so much because of its subject-matter as for the fact that it has become a milestone in the history of photography, primarily on account of its concept.It contains a new foreword written by the author and journalist Josef Moucha.

MILOŇ NOVOTNÝ

London in the 1960s

14. 2. — 11. 4. 2014

Miloň Novotný (1930–1992), a pioneer of twentieth-century Czech humanist photography, is today a classic. He is of the generation influenced by the legendary ‘Family of Man’ exhibition organized by Edward Steichen. Like Henri Cartier-Bresson, he photographed only in black and white, worked on principal with a Leica, and was a photographer of the ‘decisive moment’. Though his oeuvre includes photographs, for example, of the funeral of Jan Palach (who, in protest against the Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia and the apathy of other Czechoslovaks, set himself on fire in 1969), the focal point of his work is definitely not reportage. He was a photographer-poet of everyday life, with an extraordinary ability to perceive the profound humanity in seemingly banal scenes.

Miloň Novotný (1930–1992), a pioneer of twentieth-century Czech humanist photography, is today a classic. He is of the generation influenced by the legendary ‘Family of Man’ exhibition organized by Edward Steichen. Like Henri Cartier-Bresson, he photographed only in black and white, worked on principal with a Leica, and was a photographer of the ‘decisive moment’. Though his oeuvre includes photographs, for example, of the funeral of Jan Palach (who, in protest against the Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia and the apathy of other Czechoslovaks, set himself on fire in 1969), the focal point of his work is definitely not reportage. He was a photographer-poet of everyday life, with an extraordinary ability to perceive the profound humanity in seemingly banal scenes.

Novotný came from a family in rural Moravia. He was completely self-taught as a photographer, and was thus, fortunately, not influenced by any art education in his creative development. In 1956, he went to Prague to meet Josef Sudek (1896–1976) and ask him to select photographs for his first exhibition in Olomouc. The two photographers, each from a different generation, soon developed a lifetime friendship. A year later, Novotný moved to Prague, working, for example, on the magazines Kultura (The Arts) and Divadelní noviny (Theatre news), and photographing theatre, mainly the Činoherní klub. He published about 500 photos a year, and used most of the earnings to travel.

With the implementation of the ‘normalization’ policy of the re-established hard-line Communist régime months after the Soviet-led military intervention, Novotný found himself blacklisted. His photos could no longer be published in Czechoslovak periodicals and he was not permitted to take photographs even for theatres. He therefore earned a living mainly by making portraits of musicians for the Association of Czechoslovak Composers, but that could hardly satisfy his creative ambitions.

After the collapse of the Communist régime in November 1989, Novotný began to travel the world again. When he celebrated his sixtieth birthday, it seemed that nothing could slow down the rapid opening up of his potential as a photographer. Unfortunately, he was to live only two and half more years. The few superb photos he succeeded in bringing back from his last trips, however, are evidence that he truly deserves his reputation of being one of the best Czech photographs right to the end of his life.

Novotný became part of the history of Czech photography with his outstanding book Londýn (London), which could be published in Communist Czechoslovakia in 1968 thanks to the more relaxed atmosphere of the Prague Spring. The photos included in this project, however, were not publicly shown till 2002, in an exhibition to mark the tenth anniversary of his death. Unfortunately, the exhibition, held in the Prague House of Photography, became a victim of the August floods soon after it opened, and the exhibition had to close early. Leica Gallery Prague is thus presenting this set, legendary in the history of Czech photography, in a renewed première. Concurrently with the exhibition, KANT is publishing a re-edition of Londýn, with a new preface by the photographer and critic Josef Moucha.

Dana Kyndrová, Curator

Exhibition: London in the 1960s

Since yesterday there is a new exhibition at the Leica Gallery in Prague by a Czech photographer Miloň Novotný. It consists of street photographs from sixties London. And - similarly to the previous exhibition by Elliott Erwitt - it is short and nice :)

Od včerejška je v Leica Galerii v Praze nová výstava českého fotografa Miloně Novotného, která se skládá ze záběrů pouličního života šedesátých let v Londýně. A - podobně jako předchozí výstava Elliotta Erwitta - je krátká a milá. Takže jestli máte rádi street photography a/nebo Londýn, určitě si tam skočte :)

"London's stellar era, when it profited from its status as the capital of a wealthy empire, remained inscribed in architectual monuments and resonates with the curious contrast of its genius loci. For all that, the decay, of sorts, that had descended on the megacitywas reflected in the souls of its inhabitants. Miloň Novotný was able to distinguish this and convey it in his singular way."

"Hvězdná éra, kdy Londýn těžil z postavení hlavního města bohaté říše, zůstala vepsána v architektonických památkách. Jistá zašlost megalopole se ovšem promítá do duší jejích obyvatel. Miloň Novotný to dokázal rozeznat a osobitě podat."

See also