Top of the shots: photographers’ favourite photobooks

Which photobook would the world’s best photographers grab in a fire? Nan Goldin, Martin Parr and more pick their all-time favourites

Nan Goldin

Pioneer of a viscerally intimate diaristic style.

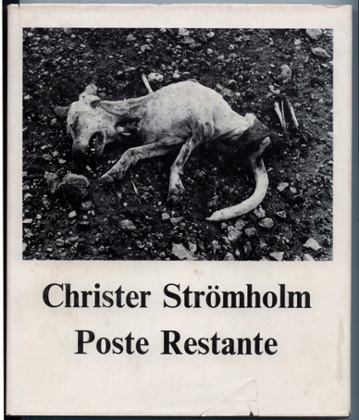

I was obsessed with Christer Strömholm at one point. I loved his photographs of transvestites in Les Amies de Place Blanche. But for me, his travel book Poste Restante is one of the great photobooks. Alongside Anders Petersen, he’s my favourite photographer. Christer looked into the darkness and beyond. He was humane. He never really photographed a person until he’d met them. Same as me. We had a similar attitude. I met him once. He saw my slideshow in the 1980s when he was in a wheelchair and he said: “Here is somebody with as big an ego as myself.” I once got a gig to go talk with him, but I was too fucked up. It was my relapse period. I have some regrets, not many, and that’s one.

Cristina de Middel

Her phenomenally successful Afronauts reimagined Zambia’s 1970s space programme.

The book I have spent most time with is Diana Arbus’s Revelations, published in 2003. It is a comprehensive, visually dynamic biography of a photographer I still admire and whose work remains for me as exciting as the first time I saw it. There is this gossip element with all her private pictures, notes and contact sheets. It somehow illuminates her obscure and enigmatic character. It works for me almost as a glossy magazine in a hair salon.

Oliver Chanarin

Controversial winner of the Deutsche Börse prize, with Adam Broomberg.

My favourite book is The British Dictionary of Sign Language, published by Faber and Faber in 1992. It contains 1,800 shots and is a great example of photography that’s both beautiful and useful.

Adam Broomberg

Collaborates with Oliver Chanarin (see above).

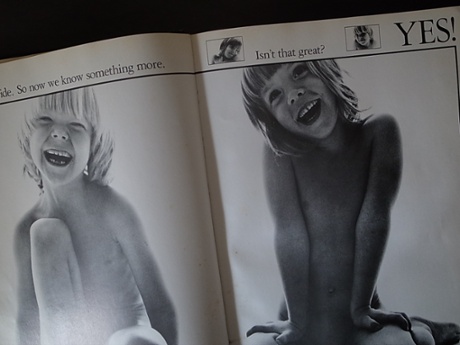

Show Me! by photographer Will McBride and psychoanalyst Helga Fleischhauer-Hardt had a profound effect on me. Originally published as Zeig Mal! in 1974, it was developed as a sex-education book, but with explicit images of sometimes pre-pubescent children engaged in sexual acts. The publishers found themselves in court for six years in the US defending it, until they finally pulled its distribution, unable to afford the legal costs.

The book is challenging on so many levels – exposing the limits of photography, society and our own moral boundaries. At best, it keeps us thinking about how society has changed in terms of how we view, touch and interact with children – as parents, friends or strangers – highlighting the state of paranoia and paralysis we are in now, where all forms of intimacy and sensuality are actively repressed through fear.

I don’t agree with any suggestion that it’s child pornography. I think what makes it such a scary read is not that anything depicted in the book is wrong (we all played doctor with our next-door neighbours). It’s just the fact that such important, intimate and private moments in growing are captured on film and widely distributed. Maybe it’s a reminder that these moments are meant to remain private, especially in a world where everything is now documented.

Bruno Ceschel

Founder of online publishing house Self-Publish Be Happy.

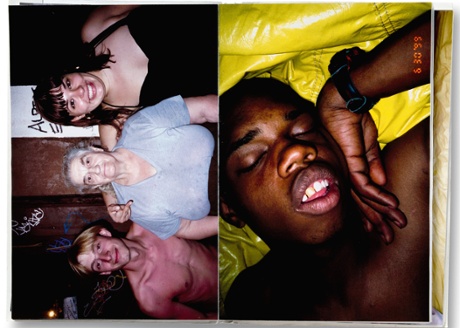

Every once in a while, a book comes along that transcends its own content. It appears at the right time and place, embodying the zeitgeist. That’s what Ryan McGinley’s The Kids Are Alright did. It rehashed things that were the tropes of youth for my generation: hedonism, pleasure, sex, drugs, nihilism. I remember picking up a copy in a New York bookshop in early 2000. It spoke to me. It put in pictures the new fluidity of identities, the pleasure of experimenting with drugs and sex.

Martin Parr

Famous for his garish documentation of everyday British life.

No book has had a greater impact on photography than William Klein’s New York 1954-55. It sent ripples of awe and amazement round the photography community worldwide, as they digested the grainy, full-bleed, bold images of the city. From Tokyo to Buenos Aires, from London to Madrid, it changed the way photographers worked.

Juergen Teller

Fashion photographer known for his harsh, flash-lit style and nudes of Kate Moss.

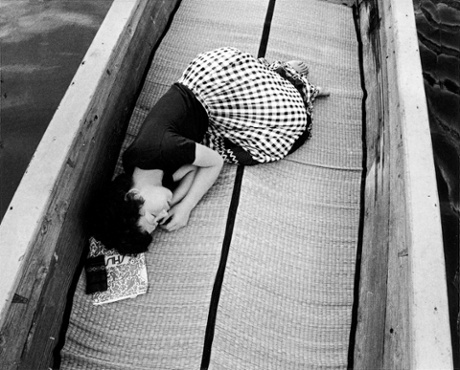

Sentimental Journey by Nobuyoshi Araki [who documented his relationship with his wife Yoko, from their honeymoon in 1971 to her death in 1990] is beautiful, sentimental, heartfelt, full of love, full of life, full of death, sad, hopeful. It’s life, not a stupid photobook.

Nobuyoshi Araki - Diary sentimental journey from Matej Sitar on Vimeo.

Paul Graham

Award-winning documentary photographer-turned-fine artist.

Volker Heinze’s Ahnung (Foreboding) was about Berlin in the late 1980s, when the wall was still up. Great images, shallow focus, details that are pointless to describe: a gate, a pipe’s shadow, a girl’s fingers. But really it’s not about Berlin so much as a state of mind, a point of time in the walled-off city.

We were close friends and shared an apartment in Berlin, working together and roaming the city. I was present when he took many of the images (and am in one). He was around for some of mine, which ended up in my New Europe book, so there is that sweet memory of freedom and fertile youth. He designed the book and struggled to find a way to print it – this was before digital presses, so it was expensive. But he managed. Just 1,000 copies. All gone now.

Viviane Sassen

Dutch star of fashion photography.

My favourite photobook is my first private album, which my mum made for me. Does that count? Probably not. Eyelids of Morning then, by Peter Beard, about the Turkana tribespeople who live side by side with Nile crocodiles. It was one of the first photobooks I ever laid my hands on.

Brett Rogers

Director of the Photographers’ Gallery, London.

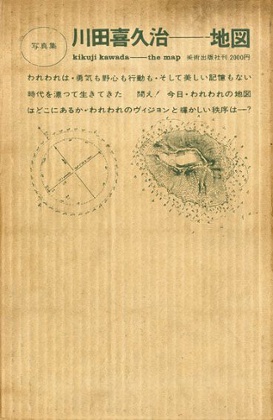

Kikuji Kawada’s The Map exemplifies what I seek in a photobook: it provides a radical new way of reading photographic images. Here, it was the experience of turning page after page of stark monochrome images, like a survivor coming face to face with the evidence and ruins of the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima. A deeply moving and highly original investigation into a seminal moment in Japanese history.

Pieter Hugo

South African photographer who has tackled the paradoxes of life there.

In 2002, I was feeling constrained with the political pressures and so-called responsibilities one has as a “South African documentary photographer”. The field had such a limited lexicon: I was constantly reiterating the same ideas and functions. It felt more like propaganda. Then I found Case History by Boris Mikhailov [capturing the social disintegration that followed the break-up of the Soviet Union]. Calling it a breath of fresh air seems like a gross understatement. It was more like a hurricane, and it cleared away the cobwebs. It maintained the observational quality of documentary, but introduced a theatrical element. It is raw and transgressive, but in a fresh and stimulating way. A book that made me re-evaluate my whole approach.

Mishka Henner

Famed for recontextualising found images, including a series on sex workers taken from Google Street View.

I have a slight obsession with a Chinese edition of Robert Frank’s The Americans. It sits on my shelf, sealed and unopened. Having made Less Américains [which erased parts of Frank’s images], I know these pictures inside-out, so there’s no need for me to look inside. But there’s a wonderful and enigmatic link between the existence of this edition and the fact the Chinese are the largest foreign owners of US debt.

Robert Frank // The Americans from haveanicebook on Vimeo.

Alec Soth

American documentary photographer, independent publisher, and artist.

About 20 years ago, on the discount shelf of my local bookshop, I discovered The Solitude of Ravens by Masahisa Fukase. This was the American reprint and the design and printing were nothing special. Taken individually, Fukase’s pictures aren’t particularly memorable, either. The book consists mostly of repetitious images of blackbirds and moody winter scenes, but Fukase’s sequencing transforms these humble pieces into the most unified and unforgettable progression of pictures I’ve ever encountered.

Simon Baker

The Tate’s first curator of photography and international art.

Ilya Ehrenburg’s 1933 book My Paris is both a photobook and extended essay on that most photographed of cities. It begins with an incredible combination of images and text, with Ehrenburg writing about “the lateral viewfinder”. This ingenious device, he explains, is intended to avoid the unfortunate effect of the camera lens, which “scatters a crowd like the barrel of a gun”. Like a kind of periscope, it allows the photographer to face in one direction and shoot at 90 degrees to it. “People would sometimes wonder: why was I taking pictures of a fence or a road?” he said. “They didn’t know I was taking pictures of them.”

Ehrenburg’s book is as cunning and oblique as the device used to make it, turning the conventional view of Paris – all boulevards and romance – on its head. The city he depicts is one of small-time miseries, homelessness, poverty and old age. For every kissing couple, there is a sleeping drunk. He catches the capital unaware, with its hair unbrushed and its trousers down. But for all his inventory of Paris’s flaws, Ehrenburg’s work has great poetry and visual flair: it’s an unflinching, brilliant counterpoint to the visions of Paris offered by the great modernist and surrealist photographers of the time. Perfectly conceived, presented, sequenced and captioned, it blows most of Ehrenburg’s contemporaries out of the water.

Michael Hoppen

Owner of influential London gallery and avid collector.

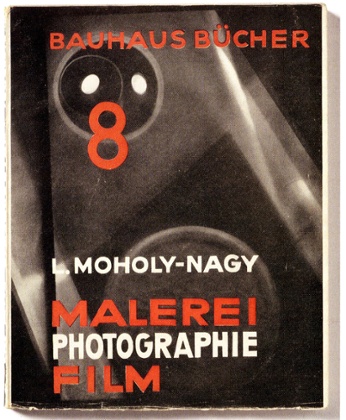

Malerei, Fotografie, Film (1928) by László Moholy-Nagy. The Hungarian’s 1928 book broke all the rules in terms of design, content and juxtaposition of photographs. This extraordinary “road map” is still subconsciously used today by many designers. He had an ability to take pictures, often from unusual viewpoints, and position them against each other in a dynamic and often unsettling way. I never get tired of looking at this book.