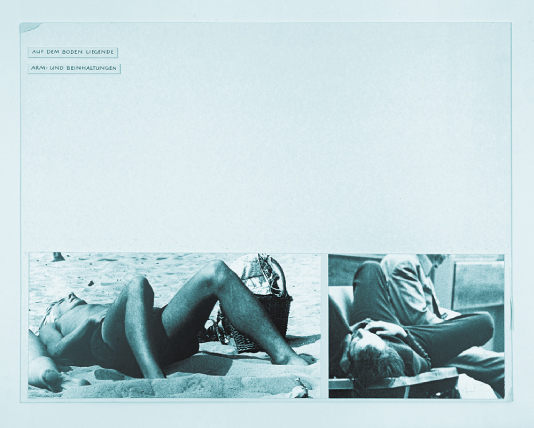

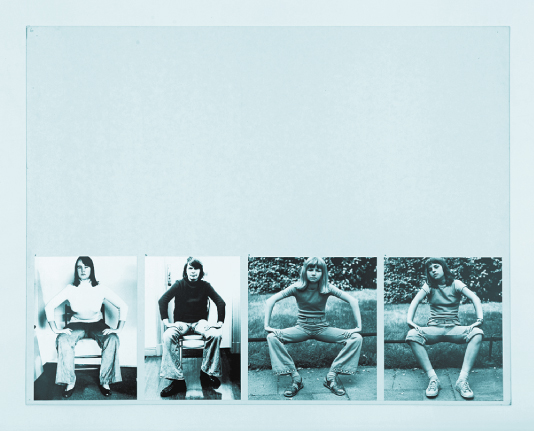

WEX, MARIANNE. - 'Let's Take Back Our Space'. "Female" and "Male" Body Language as a Result of Patriarchal Structures.

N/p,Frauenliteraturverlag Hermine Fees,1979,1st pr. Pap.366p.Ill. This English editon was edited by Pilar Alba & Virginia Garlick. Originally shown in 1977 as a photo exhibition in Berlin in connection with the show 'Women Artists International, 1877 to 1977'. The work has been expanded to include an extensive historical section.

Erik Kessels / Paul Kooiker, Terribly awesome photo books 30 x 37 cm 64 pages news paper print edition of 1000 ISBN 9789490800093

For several years, Paul Kooiker and Erik Kessels have organized evenings for friends in which they share the strangest photo books in their collections. The books shown are rarely available in regular shops, but are picked up in thrift stores and from antiquaries. The group’s fascination for these pictorial non-fiction books comes from the need to find images that exist on the fringe of regular commercial photo books. It’s only in this area that it’s possible to find images with an uncontrived quality. What’s noticeable from these publications is that there’s a thin line between being terrible and being awesome. This constant tension makes the books interesting. It’s also worth noting that these tomes all fall within certain categories: the medical, instructional, scientific, sex, humour or propaganda. Paul Kooiker and Erik Kessels have made a selection of their finest books from within this questionable new genre.

For several years, Paul Kooiker and Erik Kessels have organized evenings for friends in which they share the strangest photo books in their collections. The books shown are rarely available in regular shops, but are picked up in thrift stores and from antiquaries. The group’s fascination for these pictorial non-fiction books comes from the need to find images that exist on the fringe of regular commercial photo books. It’s only in this area that it’s possible to find images with an uncontrived quality. What’s noticeable from these publications is that there’s a thin line between being terrible and being awesome. This constant tension makes the books interesting. It’s also worth noting that these tomes all fall within certain categories: the medical, instructional, scientific, sex, humour or propaganda. Paul Kooiker and Erik Kessels have made a selection of their finest books from within this questionable new genre.

Wide Stance

Marianne Wex's timeless exploration of gender and space.

Marianne Wex's timeless exploration of gender and space.

We’ve all seen it. The guy on the subway or bus who reclines into his seat and luxuriously spreads his legs as if no one else were there. In fact, there’s a woman on either side of him, and both of them twist and tuck their legs away, bunch their handbags into their laps, squeeze their arms around themselves, and very likely glare silently in his unwitting direction.

The masculine prerogative to take up space is well documented. In nature specials, dulcet-toned voiceovers explain how male apes work their swagger as visual proof of confidence and power for onlooking potential mates. Instructions on “passing” for trans men regularly include helpful tips like “Take up as much space as possible.” A Swedish blogger recently started the blog Macho i Kollektivtrafiken (Macho on Public Transportation) to document the daily instances in which men’s propensity for voluminous space-taking on buses and trains impinges on the non-men who share the world with them.

Meanwhile, women have long been conditioned to do exactly the opposite. From Emily Dickinson (who once wrote to a male friend that “I have a little shape…. It would not crowd your desk, nor make much racket as the mouse that dens your galleries”) to the beauty culture that has nearly always deemed the thinnest, smallest, and, frequently, palest, women to be its most desirable and valuable, the message is that the measure of a lady can be taken by how little of the world she takes up.

So can we read the body’s journey through the world as an unequivocally gendered one? It would be easy enough to shrug and say yes, but for German artist Marianne Wex, that wasn’t quite sufficient. In the mid-1970s, Wex, a painter, became fascinated with body language as text, and began amassing a collection of candid photographs—most of them taken on the streets of her hometown of Hamburg, unbeknownst to their subjects—and started building a taxonomy of the differences between male and female body language. To these, she added images culled and re-shot from a variety of secondary sources, including advertisements, catalogs, art reproductions, television and film stills, pornography, and found photos; later, she photographed volunteers in poses that she considered typical of the sexes.

The first result was a project deliberate in its blurring of the line between research and art. Wex’s initial collages—rows of numerous “male” and “female” images on large white boards and headed with mundanely descriptive categorizations (“men sitting,” “women standing”)—were stark and clinical. She cropped each image so that the figures were not contextualized in space, but only readable in contrast to the images around it.

The second result was her book called Let’s Take Back Our Space: “Female” and “Male” Body Language as a Result of Patriarchal Structures. Its landscape format reproduced Wex’s large panels of grouped images and included brief blocks of text that fused art history, sociology, and personal experience into a cohesive and powerful whole. Though the book’s layout echoed the original panels and grouped images with similar workaday language (e.g. “Standing persons, arm and hand positions”), the book wasn’t simply a catalogue of gendered body language. Mike Sperlinger, who curated a 2009 Wex exhibit at London’s Focal Point Gallery, calls Let’s Take Back Our Space “a photographic typology fashioned into a feminist broadside; an encyclopedia of gesture; an anthropological portrait of Hamburg in the 1970s; a monomaniacal tract on art history; a neglected classic of appropriation aesthetics; an autobiography; an exorcism.” Indeed, for Wex herself the polemic weight of the project proved to be career-changing; after its publication, she stopped making art and chose instead to concentrate on “creating new forms with other women,” which in her case took the form of working as a healer.

A resurgence of interest in her work began, recalls Wex, when a friend of Sperlinger’s happened on a copy ofLet’s Take Back Our Space in a used bookstore and sent it to him. The intrigued critic tracked Wex down (“I suppose he used the Internet,” she shrugs), and asked if she’d be interested in showing the original panels. But to pose the rediscovery of Wex’s work—Portland, Oregon’s Yale Union Contemporary Arts hosts the United States’s first exhibition of it through December 15—as a reclamation of second-wave aesthetic activism seems like a betrayal of the artist’s own wishes, given that Wex abandoned even her own analysis as “based on artistic and scientific methods that have been totally derived from men’s interests.”

And yet it seems important to acknowledge how Wex’s work dovetailed, and continues to resonate, with a society that remains mired in assumptions about what actions, behaviors, and presentations “fit” notions of gender, and with people whose awareness of their own gendered beings is in part determined by the spaces in which they live and move. Even the quotation marks with which Wex set off “Male” and “Female” in her book’s subtitle have an enhanced significance today. Though she may have originally intended the quotes as an escape hatch for her own essentialism—the figures she photographed were always instantly readable as “men” and “women” even before their body language was parsed—they now denote the evolution that followed in the post-’70s decades, in which gender’s fluidity has become both more understood and less remarkable.

At Yale Union’s opening night for “Marianne Wex: An Exhibition,” I ask Wex, who has traveled from her home in Höhr-Grenzhausen for the event, how it feels to have her work rediscovered. She thinks, then chuckles. “Why not? I’m still rediscovering myself.”

All images courtesy YU Contemporary Arts. Andi Zeisler is Bitch Media’s editorial/creative director.

Video from a solo performance on December 11, 2012 at Reel Grrls in Seattle. The piece is inspired by Marianne Wex’s 1972-1977 photographic archiveLet’s Take Back Our Space: “Female” and “Male” Body Language as a Result of Patriarchal Structures. It explores how body language relates to gendered social expectations, how our internalized expectations of ourselves and each other manifest as we physically relate to space. I used my own body as a testing site for the subjective feminine; on projected video, I “performed” a female tendency to contain the body. Despite or perhaps because of this forced containment, my gestures spilled outward. Through live performance I responded to myself on video, in contrast attempting to relax my gestures into neutrality. Objects used on screen (mascara, a teacup, a candle) left drippings, residue and marks bearing witness to the process of performing my own internalized identity as a woman.

Conceived and performed for coursework with Wynne Greenwood. Documentation of the full live performance is forthcoming; the video below was projected and functioned as the anchor for my performance.