End of 2015 the Stedelijk will present the first exhibition about Seth Siegelaub, one of the key players of early conceptual art. Seth Siegelaub: Beyond Conceptual Art, shows an overview of the life and work of the art pioneer, collector and publisher.

He was a gallerist, independent curator, publisher, researcher, archivist, collector, and bibliographer. Often billed the “father of Conceptual Art,” Seth Siegelaub was—and remains—a seminal influence on curators, artists, and cultural thinkers, internationally and in Amsterdam, where he settled in the 1990s. And now the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam is organizing the exhibition Seth Siegelaub: Beyond Conceptual Art, devoted to the life and work of this fascinating yet still elusive figure.

Seth Siegelaub (New York, 1941–Basel, 2013) is best known for his decisive role in the emergence and establishment of Conceptual Art in the late 1960s. With revolutionary projects such as January 5–31, 1969, the Xerox Book, and July, August, September 1969, he set the blueprint for the presentation and dissemination of conceptual practices. In the process, he redefined the exhibition space, which could now be a book, a poster, an announcement—or reality at large, in keeping with his statement that “my gallery is the world now.” Siegelaub’s radical reassessment of the conditions of art resonated deeply with the iconoclastic views of his contemporaries Carl Andre, Robert Barry, Daniel Buren, Jan Dibbets, Douglas Huebler, Joseph Kosuth, Lawrence Weiner, and others, with whom he developed close working relationships.

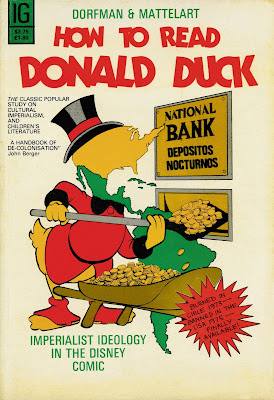

But just as these artists were gaining wider recognition, Siegelaub turned his back on the art scene and settled in Paris, where he cultivated an interest in mass media from a leftwing perspective. In line with the political mood of the times, he eventually redirected his publishing activities to scholarly research and critical essays on communication, including the bestseller How to Read Donald Duck: Imperialist Ideology in the Disney Comic (1976) by Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelart.

At the same time he pursued a lesser-known occupation as a collector of hand-woven textiles and bibliographer of books on the social history of textiles. This strand of his activity was eventually consolidated in the Center for Social Research on Old Textiles (CSROT), founded in 1986, and culminated in his authoritative Bibliographica Textilia Historiæ: Towards a General Bibliography on the History of Textiles Based on the Library and Archives of the Center for Social Research on Old Textiles (1997). During the last decade of his life, he regrouped all his projects and collections under the banner of his Stichting Egress Foundation, but simultaneously threw himself headfirst into a new bibliographical endeavor on time and causality in physics.

Acknowledging the unusual scope and essentially unclassifiable nature of Seth Siegelaub’s manifold interests and activities, the exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum will reveal to what extent his projects and collections are underpinned by a deeper concern with printed matter and lists as a way of disseminating ideas. By doing so, it will allow the wider public to reassess his role as one of the distinctive characters in twentieth-century exhibition-making while recognizing his atypical, inquisitive, and free-spirited genius.

OTHERS ABOUT SIEGELAUB

To this day Seth Siegelaub’s revolutionary views on art and exhibitions continue to shape the practices of different generations of artists and curators. Hans Ulrich Obrist, Co-director of Serpentine Gallery in London, calls him an “inspiration and toolbox,” and someone who demystified the role of curators. Ann Demeester, former Director of de Appel arts centre in Amsterdam, now Director of Frans Hals Museum/De Hallen, Haarlem, remembers the candidness with which he spoke to younger generations of curators about his historic involvement. And Charles Esche, Director of Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, suggests that “he was perhaps the first person in the art market to really understand that objects had become mere material commodities and that immaterial concepts were where the future lay—and that already in the 1960s.”

EXHIBITION

The exhibition will occupy the lower floor of the museum’s new wing and will unfold as several chapters exploring the various facets of, and connections in, Siegelaub’s work, from his groundbreaking projects with conceptual artists and his research and publications on mass media and communication theories to his interest in hand-woven textiles and non-Western fabrics. It will also highlight his collecting activity, which culminates in a unique ensemble of books on the social history of textiles and a textile collection comprising over 750 items from all parts of the world.

The Museum of Modern Art New York, which holds the bulk of Siegelaub’s collection of conceptual artworks and documentation of his New York years, has generously agreed to loan a substantial number of items to the exhibition. The world-renowned International Institute of Social History (IISH) in Amsterdam, the repository of Siegelaub’s library of 3,000 titles on media, is another major lender.

While looking back at the past, the survey will also reflect on current practices through contributions by contemporary artists, both in the exhibition and in the Public Program. Mario Garcia Torres and writer Alan Page will co-create a new work for the exhibition inspired by Siegelaub’s bibliographic project on time and causality.

In the 1990s the German conceptual artist Maria Eichhorn devised a thoroughly researched project around The Artist’s Reserved Rights Transfer and Sale Agreement, a template contract drafted by Siegelaub in collaboration with the lawyer Robert Projansky in 1971. An updated version of Eichhorn’s work will be on view in the exhibition, together with a new Dutch translation of the original contract. The museum’s Public Program will explore the issues raised by these interventions in the context of today’s art world and legal world.

Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Seth Siegelaub, Pioneering Dealer and Curator of Conceptual Art, Dies at 71

By Andrew Russeth • 06/17/13 12:45pm

Siegelaub outside 44 East 52nd Street, a temporary space where he housed the exhibition 'January 5–31, 1969.' (Photo by Robert Barry/MoMA)

Seth Siegelaub, the venturesome dealer and curator of conceptual art in New York in the 1960s and 1970s who helped lead efforts for artists’ rights and devoted his life to studying textiles, died on Saturday in Basel, Switzerland, according to a friend, confirming a report by Metropolis M. He was 71.

After closing a gallery he ran on 56th Street in Manhattan from 1964 to 1966, where he showed contemporary art and Oriental rugs, Mr. Siegelaub, still in his 20s, presented the work of artists who would become some of the core members of what would be termed conceptual art, like Douglas Huebler, Joseph Kosuth and Lawrence Weiner. He showed them in experimental curatorial formats that often eschewed gallery shows in favor of publications. In a busy period between 1968 and 1971, he organized 21 projects, according to MoMA, which holds a collection of his papers that it presented in an exhibition earlier this year. When Mr. Siegelaub donated his art-related archive to MoMA in 2011, the museum also acquired a number of works from his art collection, which included a number of important early conceptual works.

What is arguably Mr. Siegelaub’s most famous exhibition took the form of a publication, Xerox Book (1968). For that show, seven artists—Carl Andre, Robert Barry, Huebler, Mr. Kosuth, Sol LeWitt, Robert Morris and Mr. Weiner—each contributed a 25-page work. Its title was a bit misleading: though inspired by photocopying, it was made using the more traditional offset printing because of the high cost of Xeroxing at the time.

In interviews, Mr. Siegelaub often emphasized the collaborative nature of the radical advances being made in art in the late 1960s, in which he played a leading part. “This was a very collective art,” he said on a panel at MoMA in 2007, adding, “It’s not like I had these great ideas that I came up with like magic, or whatever, all by myself.”

Though many of the artists he worked with have gone on to be among the most critically and financially successful artists of the postwar period, Mr. Siegelaub said he had generally not been successful selling their art on a large scale at the time he first showed them. “I was in the research and development department…and I was never in the marketing or sales department,” he said during that panel.

“Well, you tried,” Mr. Weiner cut in, good-naturedly.

“I tried, that’s for sure,” he said, “but I never saw myself as that, and I never even thought people should make money, or could make money…I never thought that was the purpose of it.”

Seth Siegelaub was born in 1941 in the Bronx, the first of four children, served in New York State Air National Guard from 1959 to 1960, and briefly attended Hunter College in New York, before leaving to work as a plumber and part-time gallery assistant at SculptureCenter. He credited artists, particularly Mr. Andre and Mr. Weiner, art dealer Richard Bellamy, who ran the Green Gallery, and art historian and curator Eugene C. Goossen, with helping develop his interest in the latest in contemporary art.

For another seminal show, “March 1969,” Mr. Siegelaub asked 31 artists to produce a work for one day of the month, publishing the text responses of those who replied—many took the form of ephemeral works—in a book. Mr. Barry said he would release two cubic feet of helium into the air. Mr. Weiner piece read: “An object tossed from one country to another.” Claes Oldenburg’s: “Things Colored Red.” For still another show, “July, August, September 1969,” 11 artists created works throughout the world, and the complete exhibition was presented only as a publication. (Primary Information has a nice selection of digital scans of these books on its website.)

In the late 1960s, Mr. Siegelaub was involved with the Art Workers’ Coalition, a group that lobbied for artists’ rights and opposed the Vietnam War. In 1971 he published The Artist’s Reserved Rights Transfer and Sale Agreement, a contract he designed with lawyer Robert Projanksy that would pay artists a royalty fee when works were resold (assuming that a dealer and an artist both signed it). In an interview with Frieze earlier this year, the curator recalled that he began the project after hearing Mr. Barry complain about a collector reselling some of his works for a huge profit. His motivation, he said, was “to help level the playing field.”

Mr. Siegelaub left New York and the art world in 1972, moving to Paris to focus on leftist media studies and help build a library on the topic. “I was provoked into doing it by people saying that there was no theory about how the left or progressive movements use the media, despite the fact that there clearly was a history,” he told Frieze. In the 1980s, he devoted himself to assembling a library on the history of textiles. He moved to Amsterdam in 1990.

In a 2000 interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist (whose ongoing Do It project owes a debt to Mr. Siegelaub’s book exhibitions), Mr. Siegelaub explained, in part, why he stopped curating contemporary art. “If one is involved with the art world and you are not an artist but an organizer…it basically means finding young artists who you work with successfully, and then either continuing your successful project with them, or trying to do it again with another group of young artists based on your experiences and especially the contacts you made the first time,” he said. “Having done that once, for me, it didn’t seem interesting to do it again—either then in 1972, and certainly not today.”

Despite venturing beyond art in his 30s, art types remained interested in him, and he periodically appeared on panels or assisted art historians with various research projects. “From time to time I’m called back into the art world to do a service, another tour of duty or something like this, but basically I’ve had very little to do with the art world, and, well, that’s that,” he said at the MoMA panel, commenting that the art world had changed tremendously since he was involved with it—”the size, the amount of galleries, the amount of artists, the psychology of artists making art, the kind of models, sort of from the fashion world and things like this that have been imposed on the creation activity, how the territory of art making for individual artists has been very, very constrained.”

He was also vocal in interviews and writings about his frustration with the way art history is often written. “The determination of quality—who remains, who is forgotten—is very much, well, about power, in a way,” he said. “And I must say I’m quite cynical about that.”

Talking in Artforum last year, on the occasion of a show of his textiles collection at London’s Raven Row gallery, Mr. Siegelaub explained his interest in the subject: “I was intrigued by this specific relationship between beauty and commerce, but I was also struck by the fact that, unlike artmaking, the production of textiles is a social activity—it is always a collective endeavor.”

Though he had mulled trying to help develop an encyclopedic collection of textiles, he said that he quickly realized that would be impossible. “I’ve been under the illusion that somehow it would be possible to have a complete collection of books on the history of textiles, whereas a comprehensive archive of the objects themselves is definitely impossible,” he said in that same interview. “I am very far from accomplishing my goal, and perhaps I never will. It’s something that can be done, however. Most likely by someone who’s crazy and rich enough to really do it.”

He is survived by his longtime partner, Marja Bloem, and three children from previous relationships. (Raven Row has a comprehensive chronology of his career.)

In his Frieze interview from earlier this year, art writer Vivian Sky Rehberg asked, “Do you believe in art, Seth?” He replied:

I believe that art can increase our awareness of the world around us. When I was young and active in the art world, I thought the most interesting art was that which asked questions, which was on the very edge of what might even be considered art. For me, that was the definition of art; it wasn’t about having a painting hanging on the wall in your house.

(Image via MoMA’s website for its 2013 exhibition “‘This Is the Way Your Leverage Lies’: The Seth Siegelaub Papers as Institutional Critique”)

De schatkamer van Seth Siegelaub

Stedelijk Museum Seth Siegelaub was een van de aanjagers van de conceptuele kunst, maar hij bleef altijd op de achtergrond. Het Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam haalt hem met een tentoonstelling naar de voorgrond.

Janneke Wesseling 19 december 2015

Wie of wat was Seth Siegelaub? In een interview in 1969 omschreef hij zichzelf als „een punt waardoor veel informatie naar binnen en naar buiten gaat”. Hij was géén kunstenaar, geen tentoonstellingsmaker, geen uitgever. Toch heeft hij, altijd op de achtergrond, beslissende ontwikkelingen in gang gezet in de kunstwereld en in de geschiedenis van de kunst.

Wat Siegelaub (New York 1941-Bazel 2013) in ieder geval wél was: een verwoed verzamelaar en archivist. Van links georiënteerde en kritische geschriften over massacommunicatie en de media; van duizenden nieuwe en antiquarische boeken over de geschiedenis en de technieken van textiel; en van stukken textiel en hoofddeksels van over de hele wereld. Zijn textielverzameling omvat ruim 280 stukken Europese zijde uit de 15de tot de 18de eeuw en honderden weefsels uit Europa, Azië en Afrika.

TENTOONSTELLING

Seth Siegelaub: Beyond Conceptual Art. In het Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam.

T/m 17 april 2016. Dagelijks 10-18 uur, di tot 22 uur. inl: www.stedelijk.nl

Lawrence Weiner, ‘Gloss white lacquer, sprayed for 2 minutes at 40lb pressure directly’ (1968).

In de kunstwereld staat Siegelaub bekend als organisator van de vroegste tentoonstellingen van conceptuele kunst. Siegelaub trok radicale consequenties uit de opvatting dat een kunstwerk in de eerste plaats een idee is.

Na enkele jaren als klusjesman voor een aannemer gewerkt te hebben, ontdekte hij zijn organisatietalent toen hij tentoonstellingen mocht maken voor de galerie van het Sculpture Center in New York, waar hij een blauwe maandag cursussen beeldhouwen volgde. In 1964 opende Siegelaub een eigen galerie. Hier richtte hij zich op het werk van Robert Barry, Douglas Huebler, Joseph Kosuth en Lawrence Weiner, kunstenaars die wereldberoemd zijn geworden met ‘immateriële’ en ‘procesgerichte’ kunst.

Bleekmiddel

Op de aan Siegelaub gewijde tentoonstelling in het Stedelijk Museum zijn deze eerste tentoonstellingen gereconstrueerd. Aanvankelijk exposeerde Weiner nog schilderijen, maar al snel ging hij over op kunstacties, zoals ‘Een hoeveelheid bleekmiddel gegoten op een tapijt’. Siegelaub besloot dat voor dit soort kunst geen specifieke ruimte nodig is, geen ‘white cube’ zoals de kunstgalerie, maar dat deze kunst overal kan plaatsvinden: op de campus van een universiteit, in de vorm van een presentatie op een conferentie, of in een boek. In 1966 sloot hij dan ook zijn galerie onder het motto: „Van nu af aan is mijn galerie de wereld.”

Voor Inert Gas Series (1969) liet Barry vijf verschillende soorten gas ontsnappen op verschillende plekken rondom Los Angeles. Het enige ‘bewijs’ dat dit werk had plaatsgevonden, was een poster die Siegelaub liet drukken, met een telefoonnummer dat de beller verbond met een bandopname van een beschrijving van de gebeurtenis. Zijn netwerk en adreslijst was zijn belangrijkste kapitaal, zei hij.

Armand Mattelart and Ariel Dorfman, ‘How to Read Donald Duck, Imperialist Ideology in the Disney Comic’

Jack Wendler speaks about the XEROX BOOK from Kadist Art Foundation on Vimeo.

Het Xerox Book (1968) geldt als een van de belangrijkste momenten in de geschiedenis van de conceptuele kunst. Siege-laub noemde dit boek, dat nu als facsimile is herdrukt, „zijn eerste grote groepstentoonstelling”. Het boek is een tentoonstellingsruimte die plaats biedt aan werk van zes kunstenaars, waarbij iedere exposant de beschikking kreeg over 25 pagina’s. Barry leverde het gefotokopieerde werk One Million Dots, als raster afgedrukt op 25 pagina’s. Carl Andre laat van 1 tot 25 gefotokopieerde vierkantjes over de pagina’s dwarrelen en Kosuth beschrijft in korte regels, precies midden op de pagina gedrukt, de verschillende aspecten van het Xerox Book, als een tentoonstelling in een tentoonstelling.

Donald Duck

In 1970 had hij genoeg van de kunstwereld en verhuisde Siegelaub naar Parijs om zich te engageren met linkse denkers. Hij verdiepte zich in theorieën over arbeid, commercie en industrie en was directeur van de International Association for Mass Communication Research. Hij publiceerde onder meer de Engelstalige editie van het kritische boek van Ariel Dorfman en Armand Mattelart: How to Read Donald Duck: Imperialist Ideology in the Disney Comic (1975).

Siegelaub was een gepassioneerd pleitbezorger van „de dematerialisering van het kunstobject”, zoals de titel luidt van het bekende boek van Lucy Lippard, de feministische kunsthistoricus met wie hij in New York enkele jaren het leven deelde. Als het kunstwerk idee geworden is, valt er dan wel iets te zien of te beleven op de tentoonstelling van Siegelaub? Ja, heel veel. Het is een misverstand te denken dat een conceptueel kunstwerk geen herkenbare beeldende vorm zou hebben of geen fysieke gedaante, hoe miniem die soms ook mag zijn. Juist het uitgeklede karakter van deze kunstwerken, hun precieze en minimale materialisering, doen een appèl op de verbeelding. Deze kunst schept ruimte in het hoofd en richt de blik op een nieuwe manier op de wereld.

De wereld is mijn galerie

Seth Siegelaub

Siegelaub was verzot op lijstjes, drukwerk, catalogi, op oude handboeken en encyclopedieën. Ze zijn de materiële uitdrukking van de arbeid van het systematisch ordenen, het in kaart brengen van de wereld – nee, van het universum. Het is een arbeid die een grote esthetische aantrekkingskracht heeft. Dit samengaan van esthetiek en arbeid, en de sociale betekenis daarvan, is ook precies wat Siegelaub fascineerde aan textiel, zowel wat betreft het productieproces als het gebruik. Mode interesseerde hem niet, en de restauratie van de kostbare stukjes brokaat en linnen evenmin. Juist de sporen van gebruik maken het fragment van een 5de-eeuwse wollen Egyptische tuniek met decoratieve geometrische band of een 16de- eeuws geborduurd Italiaans lakentje waardevol.

Niet alleen in zijn fascinaties, ook in zijn manier van leven demonstreerde hij deze mengeling van maatschappelijk engagement, slim ondernemerschap en visionair denken. Hij financierde zijn verzamelactiviteiten met de handel in wetenschappelijke en zeldzame boeken over textiel – een handel die hem ook gelegenheid bood om verkoopcatalogi te maken.

De zeer goed ingerichte tentoonstelling Beyond Conceptualism, alsook de bijbehorende catalogus die vormgegeven is door Irma Boom en die vermoedelijk nu al een collector’s item is, zijn een onuitputtelijke schatkamer. Een labyrint waar je als bezoeker helemaal in kunt verdwijnen en steeds weer nieuwe paden en nooit vermoede schatten zal ontdekken.