Matthew Sleeth: Tour of duty. Winning hearts and minds in east timor. 2002.

Hardie Grant Publishing, South Yarra, Victoria in Kooperation mit M.33, Balaclava, Victoria, Australia, 2002. Australische Originalausgabe. Erstausgabe. Signiert von Matthew Sleeth! Martin Parr, The Photobook, vol 2, Seite 235 und 257. Paperback (as issued). 280 x 240 mm, 112 Seiten. 97 Farbfotos. Text von Paul James; edited von Helen Frajman; design von Matthew Sleeth.

What we mostly saw in our press and on TV was either the genuinely abject plight of the East Timorese on the one hand and on the other, the heroic InterFET peacekeepers coming in to save the day. Media presentation and publicity of the Australian presence was carefully orchestrated and milked for every patriotic possibility.

Sleeth uses the visual vocabulary of traditional documentary photography and disturbs and undermines it with techniques and angles borrowed from cinema. His vivid colours and jaunty angles humorously yet incisively track the Australian army and the accompanying media and entertainment caravan in Timor to form an impression quite unlike the one we have received from our mainstream press.

A far more complex view emerges, formed of multiple layers of meaning. The East Timorese people are not featured as victims as they often are in traditional photojournalism, nor are they bit players in their own redemptive drama. Instead we are given a challenging body of work, which focuses rather on the construction and staging of history.

The photographs are accompanied by a five-part essay by Paul James, which discusses Australia’s national identity through the prism of past and present military engagements.

Published by Hardie Grant Books in association with M.33, Melbourne 2002

112 Pages

280mm x 240mm

Edited by Helen Frajman

For the boys

by Alistair McGhie, 1 March 2011

Soon after her marriage to Joe DiMaggio, Marilyn Monroe en route to Japan in February of 1954 took a four-day side trip to Korea and performed ten shows for 100,000 American soldiers. They were Marilyn’s first performances in front of an audience and she said that the reaction of the soldiers made her realise she had really made it as a star.

Roosevelt was the first and every US president since has been the Honorary Chairman of the USO. George Bush Senior said that ‘the USO is how America says thanks to those serving on the front lines of freedom and at home, it is a way to let them know we care and appreciate their service and sacrifice’. The rhetoric, however, does not acknowledge the origins of the organisation. Before America entered the Second World War it had begun drafting civilians and training them at bases in rural America. Under pressure to appease the locals who resented these on-leave strangers flooding into their hometowns, Roosevelt challenged six voluntary civilian agencies, the YMCA, YWCA, National Catholic Community Service, the National Jewish Welfare Board, the Traveler’s Aid Association and the Salvation Army to organise recreation for the servicemen. The USO’s formation was partly public relations and partly to get the soldiers out of bars and into church groups.

In the Iraq–Afghanistan era of unmanned drones, soldiers blogging their experiences and uploading videos to Youtube from their laptops, morale-boosting troop-thanking camp concerts are anachronistic. The link between celebrity and patriotism and the symbolism, whether it is the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders posing for souvenir photographs or Robin Williams on a stage in battle fatigues,

is as necessary, popular and potent as ever before.

is as necessary, popular and potent as ever before.

In 1999 Australian artist Matthew Sleeth went to East Timor with an art project in mind. He had been living in Belfast creating art projects around the orthodoxies of war photography and, although he concedes that at the time he wasn’t really aware of the buildup or the politics of the situation, he headed for East Timor with the intention of creating an optimistic project on the theme of redemption.

In September of 1999 Australia led a multinational peacekeeping force to East Timor to restore security following the result of the UN sponsored independence referendum. When Sleeth arrived in East Timor he realised that his assumptions had been wrong and the project took a different direction. It was apparent to him that the United Nations, Australian government and the non-government organisations were less interested in the Timorese than they were in constructing the public image of the crisis and branding their efforts for audiences back home. The disparity between what the Timorese needed and the spin, Sleeth says was never more clearly evident than the USO-style Christmas concert ‘Tour of Duty: Concert for the Troops’ that featured John Farnham and Kylie Minogue.

Bob Hope and Anita Ekberg’s 1955 show at Thule Air Force Base in Greenland was the first televised USO performance. Jessica Simpson’s 2008 USO performance in Kuwait was also a live MySpace concert. Compared by Rampaging Roy Slaven and HG Nelson, ‘Tour of Duty: Concert for the Troops’ was telecast on two commercial networks in Australia as well as being webcast. Held at Dili Stadium in front of 4 000 troops, and despite the performances stopping for the ninety-second ad breaks, the concert was described as a special Christmas present to show appreciation and support for the troops stationed in East Timor, away from their families for Christmas.

On the world stage Timor was a small conflict and the details were never clear nor well understood. Sleeth created a critique of Australia’s response to the crisis in the form of eighty photographs that can be read as filmstills for a jingoistic movie: part Australia to the rescue and part unofficial advertisement. For the project called Tour of Duty Winning Hearts and Minds In East Timor and the accompanying monograph published in 2002, Sleeth took the stencil typeface from the title sequence of the 80s American TV show set during the Vietnam War ‘Tour of Duty’.

Australia’s inexperience in the leadership role for the InterFET gave Sleeth unhindered access to the people and the places including what he describes as the PR setpiece ‘Tour of Duty: Concert for the Troops’. Two photographs of Kylie Minogue from the Tour of Duty Winning Hearts and Minds In East Timor series have become part of the National Portrait Gallery collection, gifts of Patrick Corrigan AC. With the conventions of war photography in mind, in each of the photographs Sleeth intended to create shots that looked as though they were selling a product. Seductive and with the feel of lifestyle photography his technique combines a large format camera with square format colour negatives clearly distancing his work from the snapped at a moment reportage type of war photography .Sleeth, whose background is in film, talks a lot about editing his photographs for exhibition and publication as if they were a film. Tour of Duty Winning Hearts and Minds In East Timorwas exhibited at the Centre for Contemporary Photography in Melbourne in mid-2002.

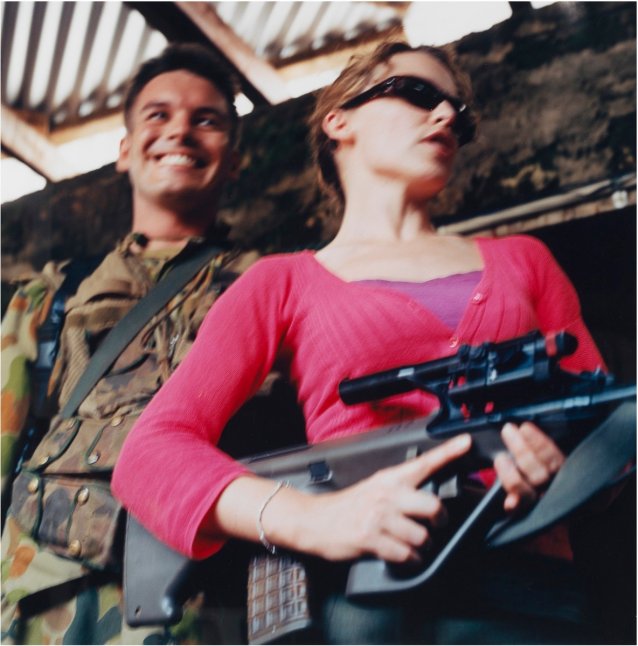

Sleeth’s photograph of Kylie posing with an Australian Army Styer rifle in a tough ‘Terminator’ stance with a beaming Australian Army Officer over her right shoulder appears to be part of the tradition of contrived images of performers ‘showing their support’ for their country’s military. For Sleeth the true narrative is an unexpected moment when the official story and the revealing subtext of the unofficial one intersect.

The soldier, who appears as if he’s ‘just happy to be there’ is Kylie’s old friend and co-star from the 1980s Australian TV show, ‘The Henderson Kids’. Kylie Minogue played the part of Charlotte ‘Char’ Kernow while Bradley Kilpatrick played Brian ‘Brains’ Buchanan. Captain Kilpatrick had deployed to East Timor as the Second in Command of B Squadron 3/4 Cavalry Regiment with InterFET in 1999. His mum had called Kylie’s mum to ask her if she’d go to East Timor as a favour to Brad. He stands behind Kylie relieved that the tense wait – the helicopter had been delayed by bad weather on its flight up to Balibo where the concert was staged – is over.

Matthew Sleeth’s project in East Timor ultimately comments not only on the repurposing of war stories for national audiences but Tour of Duty Winning Hearts and Minds In East Timor also instructs photojournalists, official war artists, freelancers, and us, the viewers, to see past the familiar imagery, clichés and contrivances derived from war to sell the role of a country in a conflict and to look more deeply into the lives of those directly affected.

MATTHEW SLEETH: WORLD VISION

Matthew Sleeth: World Vision - Art Collector

Issue 41, July - September 2007

Photographer Matthew Sleeth takes on the world. And gives back as good as he gets. It’s a perfect match, writes Edward Colless.

“There is a conflict in photography – in practice and theory – between constructing and capturing the real,” reflects Matthew Sleeth. He looks out from his panoramic studio windows across the stark, sun burnt industrial rooftops of Melbourne’s Footscray. “But,” he carefully adds, glancing back toward several large framed prints leaning against the wall of phantasmagoric street scenes from wintry Tokyo nights, “every photo is always a bit of both.”

Sleeth’s studio is up a giddying, zigzag metal staircase that hangs in a cavernous well by its fingernails off the top level of a po-mo refitted factory; a staircase that unaccountably doesn’t connect to any of the floors below in the building. The ascent is like climbing into the space shuttle while it’s waiting for lift off. You expect to look out on the horizon. And from up there you look directly down onto an old, now empty, building – waiting to be converted into more studios – that for years used to house a reception centre, specialising in Croatian weddings. “I guess people were so used to this factory being empty they never thought anyone could see them. Quite often during the night young couples would duck out for some … privacy,” he recalls. “It almost looked staged: the parents dancing upstairs, blissfully unaware of what their kids were doing in the alley exactly below them.” Look off to the right of that and you see the sizable headquarters for Lonely Planet publications. Since they built a stylishly boho café deck for their employees on their roof, Sleeth’s own view of the river and city beyond is blocked.

The scene could all be an ingenious and elegant exposition of this photographer’s own work. The fascinating celebratory manoeuvres of local, street-level culture compared to an international marketing enterprise formulating street-wise guides to the world’s localities. The chance discovery of all-too-human events right in front of you – a rich detail in a seemingly bleak or austere environment – contrasted against the stylish crafting, clarity and framing of a privileged view. From neighbourhood festivity to global entrepreneurship. From Tokyo to Melbourne. From pavement loitering to penthouse leisure. And behind it all a man gazing through the viewfinder of his window. But, of course, it’s not that simple. The real isn’t just waiting to be discovered in a dark alley. And the perspective on the world gained from a rooftop café isn’t necessarily smug, illusory or artificial. We encounter the real world but we also manufacture our encounters. We may feel we’re in the thick of things only to be disappointed at how conventional, generic or staged our photographs of it turn out. We may try to control the situation with all the muscle of a dictatorial director only to be frustrated by a scene-stealing baby or an unscripted interruption from an animal.

From Scandinavia to Japan and from Ireland to Timor, Matthew Sleeth’s photography has focussed on the world that he has been fortunate enough – and determined enough – to see. But it has also focussed from the start on what he recognises as an aesthetic argument between construction and capture. Sleeth’s graduating work in photography in the early 1990s was a portrait series of male prostitutes working the streets, with the comments of the subjects subsequently written over the prints on site. Throughout much of the 90s he was working in 35mm black and white, using lightweight Leica cameras and snapping fast. The traditional hallmarks of documentary realism. “I liked the way this allowed me to be subjective,” he explains, “and, against those 80s postmodernist methods of conceptualism and mise-en-scène photography, there’d been a resurgence of humanist photography.”

Sleeth’s first book, Roaring Days which came out in 1998, was both a summation of this on-the-run humanistic style and a conclusion to it. Gritty and hard, even in their more intimate, humble and sentimental moments, the photographs radiate a commitment to realism that feels as affectionate and agitated as it is fervent in its moral appeal to an unflinching honesty. Many of the subjects in the book are characters whose work, however, is a type of act: circus acrobats, transvestites, hookers, a rock band on tour. Even waterside workers on a picket line seem to strike a conventionally heroic, photogenic pose for the camera. They seem as histrionic as the guys horsing around in a snooker hall, or as self-conscious as a bride checking her dress out in a mirror. The real seems to be a bit of a performance.

What was expressed as a dark suspicion in his 90s work became an eloquently cool scepticism by the time of his second and provocative book, Tour of Duty. A two-week stopover in the Timor war zone en route from Ireland became a six month residency with eventually over 600 rolls of film being dispatched to a friend’s fridge in Darwin. And this was no longer 35mm black and white film. “I wanted to slow down my process,” he says. “The black and white imagery seemed disposable, too quick. For both me and the viewer. So I’d shifted over to medium format gear, and to colour. It could take several minutes to set and get a shot.” Accordingly, Sleeth’s coverage of the military activity in Timor shuns the grain and hustle associated with press photography. The troops in his photos play cricket on a beach, cheer at concerts, jostle around a barbecue, arm wrestle, read magazines, pose for photos. But this isn’t a glimpse at the human side or down-time of military action. Cameras pop up everywhere: around soldiers necks, or poking in from the side of an image of a helicopter dropping supplies. If the soldiers act like tourists at a Club Med resort, the military events seem to be choreographed displays for media coverage, almost like a lifestyle promotion. It’s the posed nature of the military intervention that is Sleeth’s real subject matter. Or more precisely, his subject is the cameras that both witness and induce events.

When, for the 2006 solo show Pictured at Monash Gallery of Art, he turned his camera surreptitiously onto anonymous tourists and passers by who were taking photos or were themselves being photographed by their companions, Sleeth folded together the divergent strategies of witnessing and triggering an event into a captivating paradox. Two Tokyo schoolgirls facing off at a Starbucks counter giggle while shyly covering their mouths as they snap each other simultaneously on their mobile phone cameras, only a few centimetres apart. What could they be photographing? Each other’s phone? Their own mirrored coyness? But this timidity seems like a performance, induced by training a camera on their friend as much as by having one pointed back at them. There’s an undeniably innocent air about this momentary exchange; but equally it’s a calculated and ritual instance of consumerism and of a commodity fetishism that fashions an identity and bond of girlpower.

Sleeth’s own sly photograph of the two of them, at a distance through a window, exploits this disarmingly cute episode with the assurance of a steady, confident voyeurism. Ironically, however, since he is photographing their public performance for their own cameras, this hardly seems a trespass. Unless, that is, we insist that what their cameras see is private. In which case, the same defence applies to Sleeth’s photo. And standing on a busy street with a bulky camera on a tripod, he’s hardly hiding. In any respect, accusing a photographer of voyeurism is like criticising their model for being exhibitionistic. Each of the photos in Pictured has this ambiguous status and vertiginous irony: Sleeth’s camera discreetly peeks around corners, over ledges or chairs to catch candid shots of people who are conscientiously posing for a photo, and lingering in venues that seem picture perfect.

“I’m interested in found narrative,” says Sleeth, “but photographed in a way where everything is so controlled that it looks staged.” Sleeth shoots in an analogue format, with very high resolution. His method over the past two years has become painstaking as well as meticulous: 20 minutes to set a shot, usually in challenging circumstances, and a minute or two for exposure. Then days of digital work on the computer screen, editing colour temperature and tone. All this to produce an image that has the rhetorical immediacy of a snapshot, a chance observation of an incident or a photo opportunity on the edge of vision, but presented on a monumental scale and with transfixing clarity. In Century Southern Tower (Shinjuku) a young woman in a track-suit top gazes into the vast neon night beyond the glass walls of the high rise executive bar where she waits for a companion whose unfinished drink sits across the table. Has this other person briefly excused themself, or have they maybe left for good? Is she petulant over the delay, idly passing time, or holding herself together having been dumped?

All these possible stories hang in the air like the miraculous lights of the city, which hover equally in the distance or in the foreground and across the whole span of the scene, bouncing around the reflective glass, and supernaturally shining through as well as onto the enframing architecture. A blurred figure to the right of the shot indicates how slow this shot’s exposure must be, which implies that this woman must be so poignantly immobilised she is oblivious to the camera. A camera – both tactfully remote but also insistently fascinated with her – that has become the unrequited gaze of her absent companion. It’s so achingly beautiful and magnificently engineered it’s hard to believe this is for real. Not a set up, not an act, not a ploy on her part to be in the picture. And it’s an enchantingly deceptive vision of the world: a world that disavows its own photogenic allure, and yet poses for us everywhere we look. ¦

Matthew Sleeth’s exhibition titled Mixed Tape will be up at Sophie Gannon Gallery, Melbourne from 7 August to 1 September 2007.

Matthew Sleeth: World Vision - Art Collector

Issue 41, July - September 2007

Photographer Matthew Sleeth takes on the world. And gives back as good as he gets. It’s a perfect match, writes Edward Colless.

“There is a conflict in photography – in practice and theory – between constructing and capturing the real,” reflects Matthew Sleeth. He looks out from his panoramic studio windows across the stark, sun burnt industrial rooftops of Melbourne’s Footscray. “But,” he carefully adds, glancing back toward several large framed prints leaning against the wall of phantasmagoric street scenes from wintry Tokyo nights, “every photo is always a bit of both.”

Sleeth’s studio is up a giddying, zigzag metal staircase that hangs in a cavernous well by its fingernails off the top level of a po-mo refitted factory; a staircase that unaccountably doesn’t connect to any of the floors below in the building. The ascent is like climbing into the space shuttle while it’s waiting for lift off. You expect to look out on the horizon. And from up there you look directly down onto an old, now empty, building – waiting to be converted into more studios – that for years used to house a reception centre, specialising in Croatian weddings. “I guess people were so used to this factory being empty they never thought anyone could see them. Quite often during the night young couples would duck out for some … privacy,” he recalls. “It almost looked staged: the parents dancing upstairs, blissfully unaware of what their kids were doing in the alley exactly below them.” Look off to the right of that and you see the sizable headquarters for Lonely Planet publications. Since they built a stylishly boho café deck for their employees on their roof, Sleeth’s own view of the river and city beyond is blocked.

The scene could all be an ingenious and elegant exposition of this photographer’s own work. The fascinating celebratory manoeuvres of local, street-level culture compared to an international marketing enterprise formulating street-wise guides to the world’s localities. The chance discovery of all-too-human events right in front of you – a rich detail in a seemingly bleak or austere environment – contrasted against the stylish crafting, clarity and framing of a privileged view. From neighbourhood festivity to global entrepreneurship. From Tokyo to Melbourne. From pavement loitering to penthouse leisure. And behind it all a man gazing through the viewfinder of his window. But, of course, it’s not that simple. The real isn’t just waiting to be discovered in a dark alley. And the perspective on the world gained from a rooftop café isn’t necessarily smug, illusory or artificial. We encounter the real world but we also manufacture our encounters. We may feel we’re in the thick of things only to be disappointed at how conventional, generic or staged our photographs of it turn out. We may try to control the situation with all the muscle of a dictatorial director only to be frustrated by a scene-stealing baby or an unscripted interruption from an animal.

From Scandinavia to Japan and from Ireland to Timor, Matthew Sleeth’s photography has focussed on the world that he has been fortunate enough – and determined enough – to see. But it has also focussed from the start on what he recognises as an aesthetic argument between construction and capture. Sleeth’s graduating work in photography in the early 1990s was a portrait series of male prostitutes working the streets, with the comments of the subjects subsequently written over the prints on site. Throughout much of the 90s he was working in 35mm black and white, using lightweight Leica cameras and snapping fast. The traditional hallmarks of documentary realism. “I liked the way this allowed me to be subjective,” he explains, “and, against those 80s postmodernist methods of conceptualism and mise-en-scène photography, there’d been a resurgence of humanist photography.”

Sleeth’s first book, Roaring Days which came out in 1998, was both a summation of this on-the-run humanistic style and a conclusion to it. Gritty and hard, even in their more intimate, humble and sentimental moments, the photographs radiate a commitment to realism that feels as affectionate and agitated as it is fervent in its moral appeal to an unflinching honesty. Many of the subjects in the book are characters whose work, however, is a type of act: circus acrobats, transvestites, hookers, a rock band on tour. Even waterside workers on a picket line seem to strike a conventionally heroic, photogenic pose for the camera. They seem as histrionic as the guys horsing around in a snooker hall, or as self-conscious as a bride checking her dress out in a mirror. The real seems to be a bit of a performance.

What was expressed as a dark suspicion in his 90s work became an eloquently cool scepticism by the time of his second and provocative book, Tour of Duty. A two-week stopover in the Timor war zone en route from Ireland became a six month residency with eventually over 600 rolls of film being dispatched to a friend’s fridge in Darwin. And this was no longer 35mm black and white film. “I wanted to slow down my process,” he says. “The black and white imagery seemed disposable, too quick. For both me and the viewer. So I’d shifted over to medium format gear, and to colour. It could take several minutes to set and get a shot.” Accordingly, Sleeth’s coverage of the military activity in Timor shuns the grain and hustle associated with press photography. The troops in his photos play cricket on a beach, cheer at concerts, jostle around a barbecue, arm wrestle, read magazines, pose for photos. But this isn’t a glimpse at the human side or down-time of military action. Cameras pop up everywhere: around soldiers necks, or poking in from the side of an image of a helicopter dropping supplies. If the soldiers act like tourists at a Club Med resort, the military events seem to be choreographed displays for media coverage, almost like a lifestyle promotion. It’s the posed nature of the military intervention that is Sleeth’s real subject matter. Or more precisely, his subject is the cameras that both witness and induce events.

When, for the 2006 solo show Pictured at Monash Gallery of Art, he turned his camera surreptitiously onto anonymous tourists and passers by who were taking photos or were themselves being photographed by their companions, Sleeth folded together the divergent strategies of witnessing and triggering an event into a captivating paradox. Two Tokyo schoolgirls facing off at a Starbucks counter giggle while shyly covering their mouths as they snap each other simultaneously on their mobile phone cameras, only a few centimetres apart. What could they be photographing? Each other’s phone? Their own mirrored coyness? But this timidity seems like a performance, induced by training a camera on their friend as much as by having one pointed back at them. There’s an undeniably innocent air about this momentary exchange; but equally it’s a calculated and ritual instance of consumerism and of a commodity fetishism that fashions an identity and bond of girlpower.

Sleeth’s own sly photograph of the two of them, at a distance through a window, exploits this disarmingly cute episode with the assurance of a steady, confident voyeurism. Ironically, however, since he is photographing their public performance for their own cameras, this hardly seems a trespass. Unless, that is, we insist that what their cameras see is private. In which case, the same defence applies to Sleeth’s photo. And standing on a busy street with a bulky camera on a tripod, he’s hardly hiding. In any respect, accusing a photographer of voyeurism is like criticising their model for being exhibitionistic. Each of the photos in Pictured has this ambiguous status and vertiginous irony: Sleeth’s camera discreetly peeks around corners, over ledges or chairs to catch candid shots of people who are conscientiously posing for a photo, and lingering in venues that seem picture perfect.

“I’m interested in found narrative,” says Sleeth, “but photographed in a way where everything is so controlled that it looks staged.” Sleeth shoots in an analogue format, with very high resolution. His method over the past two years has become painstaking as well as meticulous: 20 minutes to set a shot, usually in challenging circumstances, and a minute or two for exposure. Then days of digital work on the computer screen, editing colour temperature and tone. All this to produce an image that has the rhetorical immediacy of a snapshot, a chance observation of an incident or a photo opportunity on the edge of vision, but presented on a monumental scale and with transfixing clarity. In Century Southern Tower (Shinjuku) a young woman in a track-suit top gazes into the vast neon night beyond the glass walls of the high rise executive bar where she waits for a companion whose unfinished drink sits across the table. Has this other person briefly excused themself, or have they maybe left for good? Is she petulant over the delay, idly passing time, or holding herself together having been dumped?

All these possible stories hang in the air like the miraculous lights of the city, which hover equally in the distance or in the foreground and across the whole span of the scene, bouncing around the reflective glass, and supernaturally shining through as well as onto the enframing architecture. A blurred figure to the right of the shot indicates how slow this shot’s exposure must be, which implies that this woman must be so poignantly immobilised she is oblivious to the camera. A camera – both tactfully remote but also insistently fascinated with her – that has become the unrequited gaze of her absent companion. It’s so achingly beautiful and magnificently engineered it’s hard to believe this is for real. Not a set up, not an act, not a ploy on her part to be in the picture. And it’s an enchantingly deceptive vision of the world: a world that disavows its own photogenic allure, and yet poses for us everywhere we look. ¦