GIRLS GIRLS GIRLS

Garry Winogrand's Beautiful WomenStreet photographer Garry Winogrand's fascination with women is put on display in a new exhibit entitled Winogrand's Women Are Beautiful.

ERIN CUNNINGHAM

08.10.13 3:50 PM ET

Winogrand's WomenÃÂÃÂÃÂéTHE ESTATE OF GARRY WINOGRAND, COURTESY OF FRAENKEL GALLERY, SAN FRANCISCO

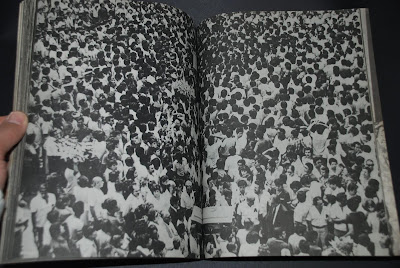

Winogrand's WomenBefore street-style photography became a major component of both fashion and art, Garry Winogrand turned his surroundings -- the streets -- and the social issues of his time into artistic images. Winogrand pioneered the "snapshot aesthetic" within the documentary photography realm, capturing a unique perspective of everday life. Although Winogrand was critiqued at times for seemingly exploiting women in his work, a new retrospective of 68 photographs entitled Winogrand's Women Are Beautiful -- based on his 1975 photo book of the same name -- celebrates, rather than criticizes, his various images of women. The images candidly capture women in everyday life, transforming their daily duties -- from parties to protests -- into beautiful works of art. Winogrand wrote in his book, “Whenever I’ve seen an attractive woman, I’ve done my best to photograph her. I don’t know if all the women in the photographs are beautiful, but I do know that the women are beautiful in the photographs. By the term ‘attractive woman,’ I mean a woman I react to, positively… I do not mean as a man getting to know a woman, but as a photographer photographing.” The exhibit opens Saturday, August 8th, at the Worcester Art Museum in Massachusettes, and runs through November 10th.

![]()

Winogrand captures one of women's most notorious traits: gossiping. The group of six women seem to have a lot to say as they lean in and whisper to each other.

Identically DressedéTHE ESTATE OF GARRY WINOGRAND, COURTESY OF FRAENKEL GALLERY, SAN FRANCISCOIdentically DressedClad in matching patterned skirts, sleeveless turtle-neck white tops, and a long pendant necklace, Windogrand photographed two girls dressed identically.

C-H-E-E-R!©THE ESTATE OF GARRY WINOGRAND, COURTESY OF FRAENKEL GALLERY, SAN FRANCISCOC-H-E-E-R!In 1974, Winogrand captures a cheerleading squad mid-act at a basketball game in Austin, Texas.

Out For a Promenade©THE ESTATE OF GARRY WINOGRAND, COURTESY OF FRAENKEL GALLERY, SAN FRANCISCOOut For a PromenadeTwo women, casually dressed, are spotted in Paris by Winogrand as they walk their dogs.

Bag Lady©THE ESTATE OF GARRY WINOGRAND, COURTESY OF FRAENKEL GALLERY, SAN FRANCISCOBag LadyWinogrand photographs a woman carrying bags down the street in 1972.

Stop The WorldéTHE ESTATE OF GARRY WINOGRAND, COURTESY OF FRAENKEL GALLERY, SAN FRANCISCOStop The WorldRallying near Central Park in NYC, Winogrand captures a series of women proudly protesting for their feminine rights -- one woman holds a sign that reads, "STOP THE WORLD, WE WANT TO GET ON!"

Ring Ring©THE ESTATE OF GARRY WINOGRAND, COURTESY OF FRAENKEL GALLERY, SAN FRANCISCORing RingLeaning inside a phone booth in NYC in 1972, Winogrand captures a woman chatting on the telephone.

La Vie ParisienneéTHE ESTATE OF GARRY WINOGRAND, COURTESY OF FRAENKEL GALLERY, SAN FRANCISCOLa Vie ParisienneWinogrand captures two women relaxing in a Parisian cafe. One woman enjoys a coffee, presumably, while the other sits with a carafe d'eau.

Hometown Glory©THE ESTATE OF GARRY WINOGRAND, COURTESY OF FRAENKEL GALLERY, SAN FRANCISCO

Hometown GloryIn his hometown of NYC, Winogrand captures a woman crossing the street in a paisley button-down, bellbottoms, and a hankerchief in 1970.

Get-Togethers©THE ESTATE OF GARRY WINOGRAND, COURTESY OF FRAENKEL GALLERY, SAN FRANCISCO

Get-TogethersSeen through a restaurant window in Boston -- which pays resemblance to a photograph -- two separate groups of women are seen enjoying a meal.

Lots of LaughséTHE ESTATE OF GARRY WINOGRAND, COURTESY OF FRAENKEL GALLERY, SAN FRANCISCO

Lots of LaughsHolding her purse and an ice cream cone, a woman is found laughing outside a store-front on the streets of New York in 1968.

“Women Are Beautiful”, the bookPosted on June 3, 2011

I finally got my hands on a real copy of “Women Are Beautiful” from Garry Winogrand. I did not buy one but found it at the Art Institute of Boston (AIB) library which is located close to Fenway park and not far from where I live. I could not borrow it so I just sat there to browse it and put it back on the shelves. I should add that the AIB library has a strong collection of photo-books, and a small exhibition room (I saw big prints from Meyerowitz on show few weeks ago).

The "Women Are Beautiful" copy at the AIB, Boston“Women Are Beautiful” by Garry Winogrand was issued in 1975 and has been a commercial failure. It is now out of print and it is really hard to find copies of it. Sometimes you might find some for sale (e.g. on Amazon) but they are very expensive. Not only it is a rare book but also – and partly because of that – it is kind of “cult”, at least in the contemporary Street-Photography circles where Winogrand is one of the most (if not the most) praised SP master. And this specific book is maybe the most emblematic – or should I say instead “problematic” – of his career, as well as the most difficult to find today.

Probably because of that the first thing that stroke me is that it is actually a little physical thing. I don’t know if another (larger) format exists (*) but the one I browsed is about 8×10 inches, with pictures reproductions inside about 5×7. It is rather thin and it has a soft cover. Actually it is very similar from the blurb book I got. For some (obvious) reasons I thought it was bigger, thicker, with a hard cover (*).

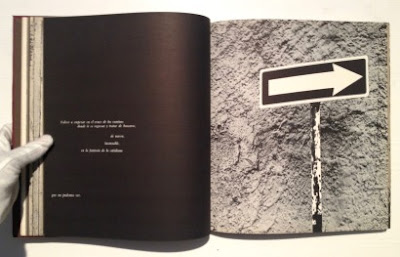

(*) note: there is another version of this book with hard cover, dust-jacket and is probably a larger format.Also it is rather banal in the way it is made. There is the short essay from Helen Gary Bishop, and then the pictures which are untitled. It looks like if it was done quickly with not too much thoughts nor craft put in it. By that I mean there is no effort to make it a “great” photo book and it probably reflects Winogrand low interest to put too much energy in making a book. Also I am not sure who did the editing, can’t remember to read something specific about that.

The pictures themselves I know almost all of them before, but never saw one in print (although I saw couple of them reproduced in other Winogrand books, such as “The Man in the crowd”). The print quality of the book is not outstanding, to say the least, which reinforces the feeling that this is definitely not a “nice” photo-book. You look at it the same way jazz connoisseurs would listen to old recordings of – say – Charlie Parker. You don’t necessarily expect too much quality in the reproduction but instead are after someone or something who/which has something to say.

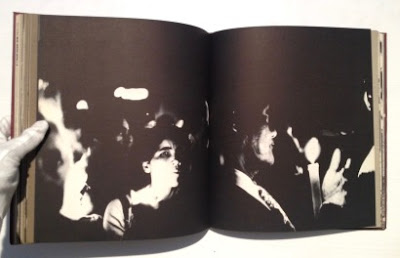

As I said before most of the image from the book are familiar to me, but looking at these photographs of women in the context of this book in hand is a rather different experience than looking at jpeg files on a monitor. Of course that is true for most photography work but in that specific case I noticed something that maybe is obvious for many but that I missed before: actually most of these photographs have the women breasts as a pivotal element. Sometimes it can be subtle, such as in this photograph where a woman is standing on the sidewalk and is seen from back, holding something in her hand whilst on the left there are dummies inside a garment store with the light falling on the fake breasts. Or it can be straight forward such as in the photograph below.

![]()

In a sense “Women are Beautiful” is almost a series of breasts photographs instead, an iteration of woman breasts, but not much in the voyeuristic sense of it. I guess it can be seen like that … or well I wondered if it is just me … but then I read the essay from Helen Bishop and at the end she elaborates about that very fact too, that the women photographed have their presence made obvious and sexual thanks to their breast (something like this, I should have noted the exact words). More specifically it appeared to me that most compositions were build with the nipples pointing somewhere whilst the eyes are directed in another direction, which kind of creates a strange twist. I believe this aspect of the images makes Winogrand work about women peculiar and sets it apart from the average – and utterly cliched – “woman in the street” photograph.

Out of the 84 images from this book there are few that I did not see before. One that really caught my attention represents a woman lying in a park but who is almost completely hidden by dogs. It is one of the very few image from the book where the presence of a woman (and her breast) is not obvious. Interestingly enough it is to the benefit of another subject matter that Winogrand liked to shoot: dogs.

Engelen van het trottoirDe Amerikaan Garry Winogrand beheerste iets onbeheersbaars: het toeval. Zijn straatfoto's behoren tot de beste die er zijn gemaakt.

Hans den Hartog Jager

21 januari 2005

Sommige fotografen zijn graag jagers. Dat zijn niet degenen die zich opsluiten in hun studio met decors en schermen en lichtmeters en make-up-assistenten. Ook niet de fotografen die hun beelden grotendeels componeren achter de computer – daar houden jagers niet van. De jagers zijn de journalisten, de nieuwszoekers, de thrill-seekers, die hun camera beschouwen als het middel om het volle leven mee te vereeuwigen. Ze vergelijken zichzelf graag met Weegee, de New Yorkse Batman-in-regenjas die in de jaren dertig en veertig van de vorige eeuw misdadigers en lijken naar de beeldenhemel hielp, of met Robert Frank, die de ziel van Amerika in zijn camera probeerde op te sluiten. Romantiek, snelheid, leven, daar houden de jagers van, en hun beelden willen daarvan een weerspiegeling zijn.

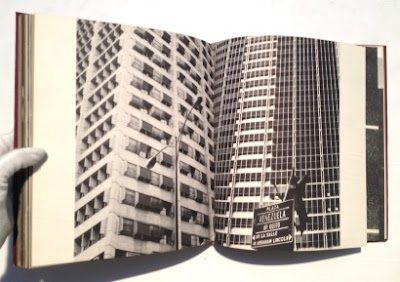

Maar hoe maak je in godsnaam een levende foto?Garry Winogrand (1928-1984) wist dat wel – en hoe. Winogrand werkte in de jaren vijftig als commercieel fotograaf, voor hij, geïnspireerd door het werk van onder anderen Walker Evans en Robert Frank, besloot zelf op straat zijn versie van Amerika vast te leggen. Van dat werk is nu in het Foam in Amsterdam een overzicht ingericht – samen met dat van collega-Street Photographers Mitch Epstein, Lee Friedlander, Joel Meyerowitz en Henry Wessel – dat om verschillende reden niet gemist mag worden. Dit vijftal behoorde tot de eerste generatie die de stad introk, niet om nieuws te vergaren of misdaden vast te leggen, maar om op beeld te jagen. Levend beeld. Beeld met betekenis. Niet voor niets is Winogrands beroemdste uitspraak dat hij fotografeerde `om te zien hoe dingen eruitzagen als ze waren gefotografeerd'. Dat is minder obligaat dan het klinkt: het toont Winogrands besef dat de fotograaf de werkelijkheid kan kleuren, keuzes kan maken, een eigen interpretatie geeft.

Daarbij werd Winogrand, eind jaren vijftig, begin jaren zestig, geholpen door de mogelijkheden van de nieuwe kleinbeeldcamera. Die maakte dat fotograferen geen ingewikkelde procedure meer was. Winogrand ging de straat op (liefst in New York) en als hij iets zag dat hem beviel – een groepje mannen en een vrouw in een auto, een jongen op een dierenshow, een mooie vrouw – stond hij stil, keek door de zoeker (maar lang niet altijd) en drukte af. Zo vaak hij maar wilde, hoogstens beperkt door het aantal rolletjes in zijn binnenzak. Die sta-en-ik-schiet-houding (en daarmee de autonome werkelijkheid van de foto) benadrukte hij nog eens door zich weinig aan te trekken van `ouderwetse' esthetische normen als een rechte horizon en evenwichtige compositie. Daar doet het echte leven ook niet aan.

Zo ontstond, met de opkomst van de eerste generatie straatfotografen een interessante kwestie: wat is, als oude esthetische normen niet voldoen, een goed beeld? Op de tentoonstelling in Foam is, intrigerend genoeg, goed te zien dat de fotografen dat zelf ook niet altijd wisten. Soms ging hun eigen romantiek met ze op de loop. Dat lijkt achteraf gezien misschien begrijpelijk (welke kunstenaar weet nu wél precies wat-ie doet?), maar die zoektocht geeft hun werk in retrospectief ook iets roerends. Zie de jager, in vol ornaat op straat, die niet weet of hij een kip of een olifant gaat schieten.

AnekdoteHet aardige is nu juist dat wij, de toeschouwers, wel kunnen zien wat achteraf het beste gewerkt heeft. En eigenlijk is dat simpel: het is altijd, zonder uitzondering het autonome beeld. Maar wat is een autonoom beeld? Als er iets boeiend is aan deze Foam-expositie, dan is het wel dat je zelden zo goed kon zien wat een goede straatfoto is, en wanneer die werkt.

De belangrijkste val, zo blijkt al snel, is de anekdote. Een beeld is geen anekdote. Dat lijkt een open deur, maar voor de man of de vrouw met een camera blijkt er weinig verleidelijker te zijn dan het vastleggen van een `gekke gebeurtenis'– men werpe een blik in het eigen vakantiealbum. De drie bijna-identieke mannen op het Franse bankje. De fiets zonder achterwiel, eenzaam aan de gracht. Het levende standbeeld. Zulke foto's worden niet gemaakt om het beeld, maar om het verhaal erachter – de foto is niet meer dan een illustratie. Hoe simpel dat besef ook lijkt, toch zwichten zelfs `kanonnen' als Epstein, als Wessel, als Meyerowitz voor het fenomeen. Zo komt Joel Meyerowitz onder andere met een stel in bijna-identieke beige regenjassen die worden weggeblazen door een enorme rookwolk uit een put (lachen!). Mitch Epstein toont een straatscène waarop een dikke politieman in een enorme gaap uitbarst (gieren!). Of een foto van vier meisjes die een reusachtige slang betasten (brullen!). Hierop zijn ook nog variaties te bedenken, zoals de foto van de man die omvalt bij de halte van een metrostation (de Lucky Luke-variant: `ik trok mijn camera en had 'm voor-ie de grond raakte!') Zulke foto's zijn flauw omdat ze het vooral moeten hebben van het verhaaltje dat je als toeschouwer zelf kunt verzinnen. Van het gevoel dat de fotograaf erbij was. Typisch een kwaal van een fotograaf die te lang over straat heeft gezworven en blij is dat hij wat meemaakt.

Een andere valkuil is de `mooie' foto. Meestal is die tegenwoordig het domein van de tweedejaars kunstgeschiedenis en/of kunstacademie, maar ook bij de straatfotografen is die niet afwezig. De `mooie foto' toont vooral de trots van de fotograaf dat-ie esthetiek in het wild heeft herkend – de zware schaduwpartij die over een straat valt, mensen die zonder het te weten op identieke afstand van elkaar staan. Het is de esthetische variant op de `gekke gebeurtenis': mooi, maar betekenisloos en in die zin net zo makkelijk als een door het toeval (of een olifant) gecomponeerd abstract schilderij.

IntellectueelWie beseft dat zulke valkuilen door de echt goede fotograaf zoveel mogelijk worden vermeden, ziet meteen dat Lee Friedlander en Garry Winogrand verreweg de beste fotografen op deze tentoonstelling zijn. Friedlander is eigenlijk het buitenbeentje, de intellectueel van het vijftal, die niet voor niets in twee aparte kabinetten hangt. Zijn werk gaat vooral over de rol van de fotograaf als manipulator – op veel van zijn foto's duikt hij zelf op, bijvoorbeeld in de beroemde foto van een vrouw met bontkraag, op de rug gezien, die zwaar overschaduwd wordt door het silhouet van de fotograaf.

Maar de meeste aandacht gaat, terecht, uit naar het werk van Winogrand. Zijn werk is zo bijzonder omdat hij iets lijkt te beheersen wat niet te beheersen valt: het toeval. Om daar iets over te zeggen is het goed te beseffen hoezeer Winogrands oeuvre, net als dat van zijn collega's, altijd het resultaat was van twee keuzes. De eerste keuze was het kiezen van het moment van fotograferen, het zoeken naar het decisive moment, waar jagende fotografen vaak lang over kunnen bomen. Toch doet dat inbreuk aan het belang van de tweede keuze: het achteraf door de fotograaf selecteren van de juiste afdrukken. Over Winogrand gaat niet voor niets de mare dat er bij zijn dood zeker 2.500 onontwikkelde rolletjes in zijn studio werden aangetroffen. Winogrand moet in zijn leven vele honderdduizenden foto's hebben geschoten, en uiteindelijk bleven er maar enkele honderden over die hij goed genoeg vond om te tonen. Dat is louter een kwestie van selectie achteraf, van nog eens kijken, nu niet meer naar de werkelijkheid, maar naar de afgeleide werkelijkheid van de foto's. Juist voor die tweede werkelijkheid had Winogrand een feilloos oog: het is opvallend hoe weinig hij trapt in de valkuil van de `gekke' of de `mooie' foto.

Dat blijkt in de eerste plaats, zij het niet eens opvallend, uit Women are beautiful (1975), bijna in zijn geheel in Foam te zien. Alle foto's uit deze serie zijn van vrouwen op straat, meestal frontaal (Winogrand was duidelijk een borstenman) in `volle actie' genomen. Uit deze serie blijkt goed hoezeer Winogrand trouw was aan zijn eigen adagium: alle vrouwen op deze foto's zijn mooi, terwijl je als toeschouwer ook beseft dat ze dat in werkelijkheid lang niet allemaal geweest zijn. Winogrand maakt ze mooi met een slimme inhoudelijke truc: hij maakt zijn vrouwen mooi door een contrast. Op opvallend veel van Winogrands Women-foto's staat wel een man met een dom gezicht of in een slecht pak, of allebei, of een paard of een groepje geile gluurders, die een schrijnende tegenstelling vormen met de jonge vrolijke, stralende vrouw. (Dat is overigens precies dezelfde truc die het Foam gebruikt om het genie van Winogrand te tonen: door hem te omringen met werk van iets mindere `soortgenoten' springt hij er nog beter uit.)

LichtbanenToch zijn de Women-foto's niet Winogrands beste. Dat zijn die paar foto's waarin vorm en inhoud, anekdotiek en esthetiek, elkaar opstuwen, op zo'n manier dat het Winogrand zelf vermoedelijk ook heeft verbaasd. Neem Los Angeles, California (1969) een foto van drie meisjes. Ze zijn jong en mooi en modieus, en de hogere krachten beseffen dat: ze geven de engelen twee meer dan vrouwbrede lichtbanen mee die stralen over het trottoir. En dat is nog niet alles: precies naast de lichtbanen, in de schaduw, staat een jongen in een rolstoel, zijn hoofd onderuitgezakt, in een machteloze houding – de drie engelen zien hem en kunnen hun afschuw niet onderdrukken. Winogrand heeft dit gezien, misschien niet eens alles tegelijk, maar in ieder geval heeft hij op het juiste moment afgedrukt.

Of neem de foto Staten Island Ferry (1971). We zien de voorkant van de boot, wit, vrolijk en vol. Alle dagjesmensen staan aan de reling, zowel op het centrale dek als op de verdieping erboven. Slechts één echtpaar is in het midden blijven staan, aan weerzijden van de paal die het bovendek ondersteunt. De symmetrie rond de paal is bijna perfect – het is een prachtige verbeelding van eenzaamheid zonder alleen te zijn.

Met zulke foto's, composities die geen composities zijn, treft Winogrand de essentie van de straatfotografie: hij ziet hoe het lot commentaar geeft op haar mensen. Dat lot is de vorm, het licht, een subtiel beeldrijm, die iets inhoudelijks toevoegen aan het beeld dat je zelf nooit zou kunnen verzinnen – niet zou durven verzinnen, zelfs. Neem de foto van een man en vrouw in de dierentuin, een echtpaar, ongetwijfeld. Zij is blond en jong en mooi als een model, hij is goedgekleed en knap en zwart. Alleen: het lot heeft ze allebei een aapje in hun armen gedrukt, twee schattige chimpanseetjes, gestoken in modieuze pakjes als gekoesterde kinderen. Het lijkt idyllisch, als de echo tussen de twee mensen en de twee apen niet tamelijk gruwelijk was; deze foto zegt iets heel sarcastisch over de relatie tussen blank en zwart, over vooroordelen en afstamming dat zich normaal alleen maar in crypto-racistische termen laat beschrijven. Misschien is dat racisme er ook wel, al kun je evengoed volhouden dat het wordt gecompenseerd door de liefdevolle, zelfverzekerde blikken van het echtpaar, het heldere licht en de olijke gezichtsuitdrukkingen van de chimpansees.

Van zulke perfecte foto's heeft Winogrand er wel zes of acht of tien gemaakt. Dat lijkt weinig, maar door de rest van de tentoonstelling wordt duidelijk dat dat er heel veel zijn. Tegelijk is het maar een fractie van Winogrands totale productie. Hoe goed hij ook was, blijkbaar had zelfs hij dit soort foto's niet helemaal in de hand, had ook hij af en toe een duwtje van het lot nodig. Maar dat was Winogrands grote kracht: dat hij het lot wist af te dwingen. Wie zijn werk ziet, krijgt de indruk dat Winogrands obsessie net even groter was dan die van zijn collega's, dat hij net even gedrevener was dan de anderen. Die werklust, dat fanatisme, zijn door het lot beloond met een aantal foto's, die horen tot het beste wat er is gemaakt.

Garry Winogrand and the American Street Photographers. T/m 30 maart in FOAM, Keizersgracht 609, Amsterdam. Dagelijks 10-17u, do en vr 10-21u. Inl. www.foam.nl

Hans Aarsman: 'Alsof je gewoon door een raam kijkt'In deel 2 van een serie over beeldend kunstenaars en de kunst die hen inspireert fotograaf en schrijver Hans Aarsman over Garry Winogrand (1928-1984).

Sandra Smallenburg

2 juli 2005

'De eerste keer dat ik een foto zag van de Amerikaanse fotograaf Garry Winogrand, vond ik er niet veel aan. Het was in 1980, en Winogrand had net zijn boek Public Relations uitgebracht, met foto's van demonstraties, feestjes en openingen. Veel van die foto's waren plat van voren geflitst, waardoor de achtergrond zwart werd. Ik vond het een soort verjaardagsfotografie. Zelf werkte ik in die tijd voor kranten, maakte journalistieke foto's vanuit een links-idealistische houding.

'Maar toen ik Winogrands foto's terugzag, greep het werk me aan. Ik was op zoek naar relativering van het links idealisme in de documentaire fotografie. Winogrand maakte documentaire fotografie, maar hij deed er iets persoonlijks mee. Hij laat ons de theatrale kant zien van het dagelijks bestaan. Dat het allemaal niet zo gewichtig hoeft. Hij kiest het meest banale onderwerp dat je maar kunt bedenken, mensen op feestjes, mensen die op straat voorbijkomen. Daarin zoekt Winogrand naar iets wat ons bestaan kan optillen.

Spoor bijster'Eind jaren '70 is Winogrand steeds losser gaan fotograferen. Op dit contactvel is dat mooi te zien. Het komt uit dé monografie over Winogrand, Figments from the Real World, na zijn dood samengesteld door John Szarkow- ski, fotografieconservator van het MOMA in New York. Szarkowski probeert in zijn boek aan de hand van dit contactvel aan te tonen dat Winogrand de laatste jaren van zijn leven het spoor bijster was. Na Winogrands dood in 1984 zijn er duizenden contactvellen en onontwikkelde films boven water gekomen. Szarkowski, een persoonlijke vriend van Winogrand, heeft al dat werk uitgezocht. Hij schrijft in dat boek dat hij zich door Winogrand eigenlijk belazerd voelde, toen hij dat late werk zag. Volgens Szarkowski deed Winogrand maar wat, klikte hij als een gek in de rondte. Voor mij bewees dit contactvel juist het tegendeel. Wat mij betreft is dit juist zijn interessantste periode.

'Mensen zien graag foto's die op schilderijen lijken. Winogrand gooide alle beeldende conventies over boord, het lijkt wel of hij ze niet eens kende. Alsof hij van de maan kwam en voor het eerst op aarde was beland. Op dit contactvel is te zien hoe Winogrand te werk ging. Je ziet hem in die auto zitten - raampje open, raampje dicht. Je voelt de beweging, het rondrijden. Hij speelt met de spijlen van de autodeur, gebruikt het kader van het raam. Of hij volgt een tijdje het trottoir, waardoor de compositie weer wat meer gekanteld is. En dan opeens ziet hij, in de verte, een vrouw met kinderwagen en stelt hij daarop scherp.

'Wat mij zo interesseert aan zijn werk is niet het onderwerp, maar de manier waarop hij kijkt, zijn grondhouding. De manier waarop hij de horizon scheef zette, is geen trucje, geen nieuwe manier om een compositie te maken. Daar was hij niet mee bezig. Het schijnt dat hij een rolletje volschoot in één of twee minuten. Dan moet hij toch steeds iets gezien hebben, er moet iets zijn wat je triggert. Als ik vroeger op reportage was, schoot ik ook wel eens vijf films per dag. Maar dan was ik 's avonds doodop van een dag lang geconcentreerd kijken. Hij deed dat elke dag, zijn hele leven lang.

Leukste foto's'Het gaat mij bij dit contactvel niet om een enkele foto, maar om het geheel. Boeken en tentoonstellingen van Winogrand vind ik vaak teleurstellend, omdat er dan weer iemand door zijn oeuvre is gegaan die denkt dat hij de beste of leukste foto's eruit gepikt heeft. Zelf was hij niet geïnteresseerd in het maken van boeken, het samenstellen daarvan liet hij vaak aan anderen over. Hij was bezig met dat geheel, met die verzameling. Hij had stapels proefprintjes, maar aan de uiteindelijke selectie kwam hij vaak niet toe. Winogrand vond dat je niet te snel naar je eigen werk moest kijken. Hij liep altijd een jaar of vijf achter met afdrukken. Toen hij doodging, was er nog steeds dat gat van vijf jaar.

'In de jaren '80 heb ik hem erg nageaapt. Ging ik opeens ook schots en scheef fotograferen en flitsen. Na een paar jaar vond ik dat toch te opvallend. De beste foto's zijn de beelden waarbij je niet voelt dat iemand voor je in de weer is geweest. Waarbij je niet denkt: wat knap, of, dat ie dat durft. Alsof je gewoon door een raam kijkt, maar er toch iets is waardoor je blijft kijken. Daarom ben ik na een tijdje heel bewust landschappen gaan fotograferen. Die foto's waren juist het tegenovergestelde van de Winogrand-fotografie. Ik gebruikte zelfs een waterpas om de horizon recht te zetten.

'Ik hou niet zo van mijn eigen foto's. Ik zou ze nooit ophangen. Schilderijen wel, dat zijn hebbedingetjes. Als je een foto ophangt, wordt het ook een hebbeding. Dat wringt. Daarom houd ik zo van Winogrand: zijn fotografie is immaterieel. Het ging hem om het idee, en dat hoort niet in een lijstje. Toch heb ik op allerlei manieren geprobeerd om dit contactvel aan te kopen. Tevergeefs, galeries zijn alleen geïnteresseerd in het verkopen van schilderijtjes. Nu trek ik het boek waarin het contactvel staat een keer of tien per jaar uit de kast, vaak om het aan anderen te laten zien. Ik heb ook een lijst met citaten van hem. Winogrand had fantastische uitspraken, zoals 'There is nothing as mysterious as a fact clearly described.'

'Er bestaat een filmpje waarin je Winogrand aan het werk ziet. Dan zie je hem zo heel losjes de camera voor zijn gezicht heen en weer schuiven. De hele tijd rommelen met dat ding, een beetje klungelig haast, net of hij jeuk had aan zijn voorhoofd. Je begrijpt ook meteen waarom hij nooit een klap voor zijn kop heeft gehad. Je hebt namelijk helemaal niet het idee dat hij aan het fotograferen is. Winogrand was klein, en net zo onopvallend als een lantarenpaal. Ik heb eens gelezen dat hij naar mensen riep die hem vragend aankeken, nadat hij ze gefotografeerd had: You've been immortalized.'

Biografie Hans Aarsman1951 Geboren in Amsterdam

1970-1978 Studie scheikunde en linguïstiek, Universiteit van Amsterdam

1980-1982 Rijksakademie

1980 Debuteert als fotograaf

1980 Werkt als freelancer voor Nieuwe Revu, De Groene en Skrien

1980 Mede-oprichter fototijdschrift Plaatwerk

1989 Fotoboek Hollandse Taferelen

1993 Fotoboek Aarsmans Amsterdam

1993 Maria Austria Prijs

1994 Roman Twee hoofden, één kussen

1995 Theatermonoloog De wijze van zaal 7

2001 Mede-oprichter fototijdschrift Useful Photography

2002 Theatermonoloog Ruis, over Garry Winogrand

2003 Fotoboek Vrrooom! Vrrooom!, met tentoonstelling in Nederlands Fotomuseum 2004 Fotoboek Onzichtbaar Gent

2004 Column de Volkskrant: De Aarsman Collectie

2005 Theatermonoloog Zeg het maar