Eugène Atget’s lost photographs of Paris

An important portfolio of images by Eugène Atget, one of the ‘founding fathers’ of modern photography, was thought to have been lost — until it was rediscovered ‘almost by chance’ among the archives of the artist André Derain

When the descendants of André Derain found a portfolio, hidden in the artist’s former Paris home, they had little idea of how important their discovery would turn out to be. Inside were works by Eugène Atget, one of the ‘founding fathers’ of modern photography, whose work had a profound influence on Derain’s own compositions.

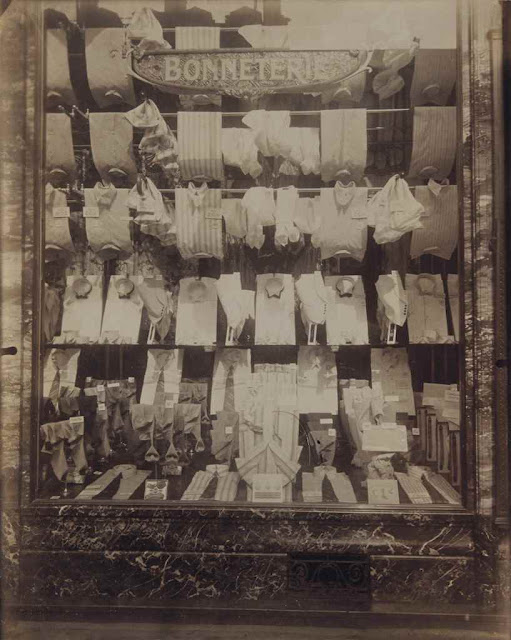

Born in 1857, Atget first began taking photographs in 1890, documenting the architecture of Paris’s streets, from door handles to monuments and shop windows. Specialist Elodie Morel explains, ‘He wanted to make an inventory of the city, which could then be used by artists in their paintings.’ Atget’s work soon caught the eye of some of the great names in art history, including Man Ray and Georges Braque, who became collectors of his work.

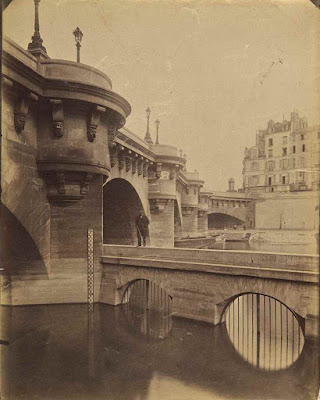

Eugène Atget (1857-1927), Pont Neuf, 1902-1903. Titré et numéroté 4654 au crayon (verso), imagefeuille 22.2 x 17.8 cm (8¾ x 7 in), (2). Estimate €8,000-12,000. This lot is offered in Photographies on 10 November 2016 at Christie’s in Paris

In this video Geneviève Taillade, André Derain’s niece, describes the moment she discovered Atget’s photographs. ‘I thought they were beautiful,’ she says, ‘but didn’t realise they had been taken by such a prestigious artist.’ Certain images in the portfolio reveal complicity between Derain and Atget, who are believed to have been friends: a photograph of the Pont Neuf (above), re-emerges at the same angle in an engraving by Derain.

‘What I love about my work is that opportunity to find links with the past — to go back in time to a bygone era, and discover a story,’ says Morel. In establishing the affinity between these two great artists, this story is also ‘a discovery for the history of photography’, she adds. ‘This collection has been referenced many times but had never seen the light of day — until now.’

Foto's Eugène Atget sprankelen nog steeds

(Un)common Places: Stephen Shore, Korrie Besems, Eugène Atget. T/m 11 mei in Nederlands Foto Instituut, Witte de Withstraat 63, Rotterdam. Open: di t/m zo 11-17u. Catalogus: ƒ 20.

Eddie Marsman

29 maart 1997

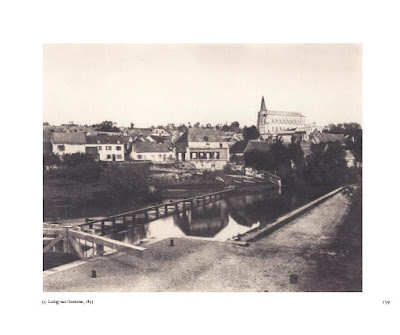

Dat fotografie zo simpel kan zijn, denk je telkens weer bij het zien van de foto's van Eugène Atget. Neem die welke hij omstreeks 1900 maakte in de rue Mouffetard in Parijs. Café Aux Vieux Chêne staat erop en, zij het maar voor de helft, een drogisterij plus het poortje naar een binnenplaats. Dat is het wel zo'n beetje. En al trekt dat café veel aandacht, je kunt niet zeggen dat de foto erover gaat - de foto gaat over alles tegelijk: in één oogopslag is het bij elkaar geveegd, zelfverzekerd en toch alsof het nauwelijks is gezien.

Op dezelfde bijna achteloze manier zou Atget enkele jaren later de rue Montorgeuil samenvatten in een foto van restaurant Au Rocher de Cancale en Hôtel Lavalette met haar waterval van stenen en houten trappen. Het is Eugène Atget in een notedop: alledaags, vanzelfsprekend en onopgesmukt.

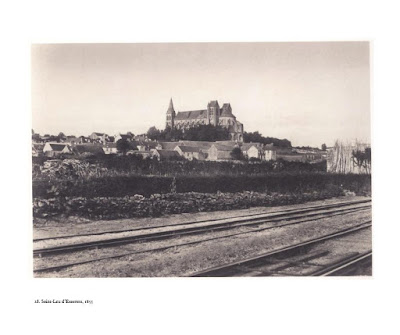

Bij leven was hij een tamelijk onbekende straatfotograaf die in de rust en het egale licht van de ochtend systematisch de straten van zijn woonplaats Parijs afschuimde, op zoek naar 'zestiende- tot en met negentiende-eeuwse architectuur in de oude straten; historische en bijzondere huizen; fraaie façades en deuren, betimmeringen en deurkloppers; oude fonteinen; houten en gietijzeren trappen; interieurs van alle kerken (overzichten en details)', aldus een in 1920 door hemzelf opgestelde lijst. Inmiddels wordt de Fransman (1857-1927) allerwege beschouwd als de voorloper van de moderne, dat wil zeggen zich van ieder schilderachtig effect afkerende, fotografie.

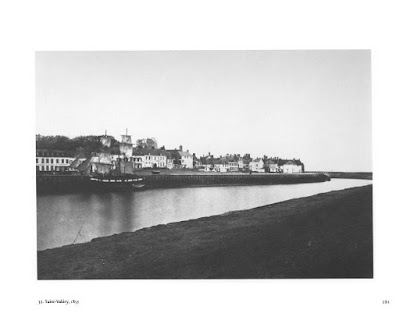

Zijn foto's vormen momenteel het hartveroverende middelpunt van een expositie in het Nederlands Foto Instituut, waarin voor het eerst (op één na) alle in openbare Nederlandse collecties aanwezige Atgets bij elkaar worden gebracht: tien foto's in totaal (op één na vintage prints), afkomstig uit het Rijksmuseum en het Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, het Van Abbe Museum in Eindhoven en het Prentenkabinet van de RU Leiden. Een tweede grote bijdrage bestaat uit een serie moderne afdrukken uit het Parijse Musée Carnavalet die een minder bekende kant van Atget laten zien; de foto's die hij maakte in de zone, de verfomfaaide rafelrand buiten de oude stadswallen met haar armoedige steegjes en geïmproviseerde bouwsels. Jammergenoeg valt het drukwerk van deze foto's vanwege het gebruik van hedendaags barietpapier (het klassieke daglichtpapier zou geëigender zijn geweest) nogal tegen: ze ogen somber en vlak, waar de oorspronkelijke afdrukken ondanks de opgetreden vergeling nog altijd sprankelen in toonschaal en detaillering.

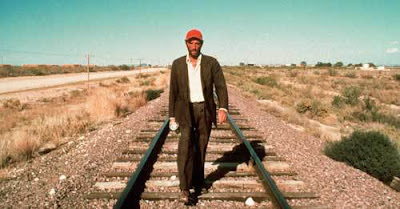

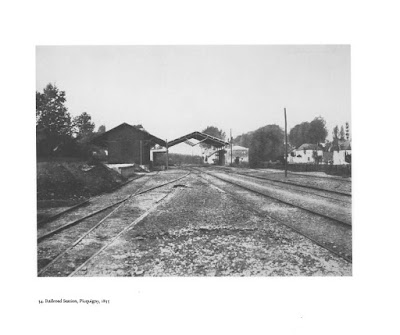

Het werk van Atget vormde een inspiratiebron voor de meest uiteenlopende fotografen, van Walker Evans in het Amerika van de jaren dertig tot het duo Bernd en Hilla Becher in het Duitsland van nu. En ook de eveneens in het NFI exposerende Amerikaanse new topographer Stephen Shore en de Nederlandse Korrie Besems hebben het nodige van hem opgestoken. Besems presenteert ruim twintig Poolse stadstaferelen in kleur, in 1995 gemaakt op plekken waar de sporen van de Tweede Wereldoorlog en daarop volgende jaren van verwaarlozing zichtbaar zijn. Van Shore zijn tachtig stedelijke landschapsfoto's uit de jaren zeventig te zien van steegjes, achtertuintjes, kruispunten en parkeerplaatsen.

Evenals Atget begeven Shore en Besems zich bij voorkeur naar onooglijke locaties en hanteren ze een onnadrukkelijke stijl van fotograferen - al krijgt het resultaat ook bij hen als vanzelf een mysterieuze aantrekkingskracht. Uncommon Places noemt Shore zijn plekken niet voor niets. Het NFI koos het als titel voor de complete tentoonstelling, zij het dat het wel het ontkennende voorvoegsel tussen haakjes plaatste; alsof iemand de subtiele essentie van het origineel zou kunnen ontgaan.

Er is een cruciaal verschil tussen de oude Atget en zijn navolgers. Zijn werk heeft een authenticiteit die vandaag de dag nog slechts te benaderen is. Want waar zijn onnadrukkelijkheid een intuïtieve was, is ze voor de moderne fotografen een doelbewust streven. Hun werk is veel nadrukkelijker gefotografeerd, zoals ook mag blijken uit de soms wat krampachtige manier waarop Shore zijn foto's van menselijke aanwezigheid probeert te ontdoen en Besems, zich schikkend in het onvermijdelijke, ze juist stelselmatig een rol geeft in het brandpunt van haar foto's. Bij Besems zoeven kinderen op skateboards over het troittoir, wordt een stoep geschrobt en zeult een man met boodschappentassen tussen het metershoge onkruid en de gehavende gevels van de Ulica Wodna. En al mag het resultaat er zijn, het geeft haar foto's een anekdotische lading die ver verwijderd is van de nulgraad van de fotografie die Atget gestalte gaf.